the Lady Taking Oath As to Her Conduct

Day 2 of the Heptameron - Tale 15

Tale 15 of the Heptameron

At the Court of King Francis the First there was a gentleman whose name I know right well, but will not mention. He was poor, having less than five hundred livres a year, but he was so well liked by the King for his many qualities that he at last married a lady of such wealth that a great lord would have been pleased to take her. As she was still very young, he begged one of the greatest ladies of the Court to receive her into her household, and this the lady very willingly did.

Now this gentleman was so courteous, so handsome, and so full of grace that he was held in great regard by all the ladies of the Court, and among the rest by one whom the King loved, and who was neither so young nor so handsome as his own wife. And by reason of the great love that the gentleman bore this lady, he made such little account of his wife, that he slept scarcely one night in the year with her, and, what she found still harder to endure, he never spoke to her or showed her any sign of love. And although he enjoyed her fortune, he allowed her so small a share in it, that she was not dressed as was fitting for one of her station, or as she herself desired. The lady with whom she abode would often reproach the gentleman for this, saying to him—

"Your wife is handsome, rich, and of a good family, yet you make no more account of her than if she were the opposite. In her extreme youth and childishness she has hitherto submitted to your neglect; but I fear me that when she finds herself grown-up and handsome, her mirror and some one that loves you not will so set before her eyes that beauty by which you set so little store, that resentment will lead her to do what she durst not think of had you treated her well."

The gentleman, however, having bestowed his heart elsewhere, made light of what the lady said, and notwithstanding her admonitions, continued to lead the same life as before.

But when two or three years had gone by, his wife became one of the most beautiful women ever seen in France, so that she was reputed to have no equal at the Court. And the more she felt herself worthy of being loved, the more distressed she was to find that her husband paid no attention to her; and so great became her affliction that, but for the consolations of her mistress, she had well-nigh been in despair. After trying every possible means to please her husband, she reflected that his inclinations must needs be directed elsewhere, for otherwise he could not but respond to the deep love that she bore him. Thereupon she made such skilful inquiries that she discovered the truth, namely, that he was every night so fully occupied in another quarter that he could give no thought to his wife or to his conscience.

Having thus obtained certain knowledge of the manner of life he led, she fell into such deep melancholy, that she would not dress herself otherwise than in black or attend any place of entertainment. Her mistress, who perceived this, did all that in her lay to draw her from such a mood, but could not. And although her husband was made acquainted with her state, he showed himself more inclined to make light of it than to relieve it.

You are aware, ladies, that just as extreme joy will give occasion to tears, so extreme grief finds an outlet in some joy. In this wise it happened that a great lord who was near akin to the lady's mistress, and who often visited her, hearing one day of the strange fashion in which she was treated by her husband, pitied her so deeply that he desired to try to console her; and on speaking to her, found her so handsome, so sensible, and so virtuous, that he became far more desirous of winning her favour than of talking to her about her husband, unless it were to show her what little cause she had to love him.

The lady, finding that, though forsaken by the man who ought to have loved her, she was on the other hand loved and sought after by so handsome a Prince, deemed herself very fortunate in having thus won his favour. And although she still desired to preserve her honour, she took great pleasure in talking to him and in reflecting that she was loved and prized, for these were two things for which, so to speak, she hungered.

This friendship continued for some time, until it came to the knowledge of the King, who had so much regard for the lady's husband that he was unwilling he should be put to any shame or vexation. He therefore earnestly begged the Prince to forego his inclinations, threatening him with his displeasure should he continue to press his suit.

The Prince, who set the favour of the King above all the ladies in the world, promised for his sake to lay aside the enterprise, and to go that very evening and bid the lady farewell. This he did as soon as he knew that she had retired to her own apartments, over which was the room of the gentleman, her husband. And the husband being that evening at his window, saw the Prince going into his wife's room beneath. The Prince saw him also, but went in for all that, and in bidding farewell to her whose love was but beginning, pleaded as his sole reason the King's command.

After many tears and lamentations and regrets, which lasted until an hour after midnight, the lady finally said—

"I praise God, my lord, that it pleases Him you should lose your love for me, since it is so slight and weak that you are able to take it up and lay it down at the command of man. For my own part, I have never asked mistress or husband or even myself for permission to love you; Love, aided by your good looks and courtesy, gained such dominion over me that I could recognise no God or King save him. But since your heart is not so full of true love that fear may not find room in it, you can be no perfect lover, and I will love none that is imperfect so perfectly as I had resolved to love you. Farewell, then, my lord, seeing that you are too timorous to deserve a love as frank as mine."

The Prince went away in tears, and looking back he again noticed the husband, who was still at the window, and had thus seen him go in and come out again. Accordingly he told him on the morrow why he had gone to see his wife, and of the command that the King had laid upon him, whereat the gentleman was well pleased, and gave thanks to the King.

However, finding that his wife was becoming more beautiful every day, whilst he himself was growing old and less handsome than before, he began to change his tactics, and to play the part which he had for a long time imposed upon his wife, bestowing some attention upon her and seeking her more frequently than had been his wont. But the more she was sought by him the more was he shunned by her; for she desired to pay him back some part of the grief that he had caused her by his indifference.

Moreover, being unwilling to forego so soon the pleasure that love was beginning to afford her, she addressed herself to a young gentleman, who was so very handsome, well-spoken, and graceful that he was loved by all the ladies of the Court. And by complaining to him of the manner in which she had been treated, she lured him to take pity upon her, so that he left nothing untried in his attempts to comfort her. She, on her part, to console herself for the loss of the Prince who had forsaken her, set herself to love this gentleman so heartily that she came to forget her former grief, and to think of nothing but the skilful conduct of her new amour, in which she succeeded so well that her mistress perceived nought of it, for she was careful not to speak to her lover in her mistress's presence. When she wished to talk with him she would betake herself to the rooms of some ladies who lived at the Court, amongst whom was one that her husband made a show of being in love with.

Now one dark evening she stole away after supper, without taking any companion with her, and repaired to the apartment belonging to these ladies, where she found the man whom she loved better than herself. She sat down beside him, and leaning upon a table they conversed together while pretending to read in the same book. Some one whom her husband had set to watch then went and reported to him whither his wife was gone. Being a prudent man, he said nothing, but as quickly as possible betook himself to the room, where he found his wife reading the book. Pretending, however, not to see her, he went straight to speak to the other ladies, who were in another part of the room. But when his poor wife found herself discovered by him in the company of a gentleman to whom she had never spoken in his presence, she was in such confusion that she quite lost her wits; and being unable to pass along the bench, she leaped upon the table and fled as though her husband were pursuing her with a drawn sword. And then she went in search of her mistress, who was just about to withdraw to her own apartments.

When her mistress was undressed, and she herself had retired, one of her women brought her word that her husband was inquiring for her. She answered plainly that she would not go, for he was so harsh and strange that she dreaded lest he should do her some harm.

At last, however, for fear of worse, she consented to go. Her husband said not a word to her until they were in bed together, when being unable to dissemble so well as he, she began to weep. And when he asked her the cause of this, she told him that she was afraid lest he should be angry at having found her reading in company with a gentleman.

He then replied that he had never forbidden her to speak to a man, and did not take it ill that she had done so; but he did indeed take it ill that she had run from him as though she had done something deserving of censure, and her flight and nothing else had led him to think that she was in love with the gentleman. He therefore commanded her never to speak to him again in public or in private, and assured her that the first time she did so he would slay her without mercy or compassion. She very readily promised to obey, and made up her mind not to be so foolish another time.

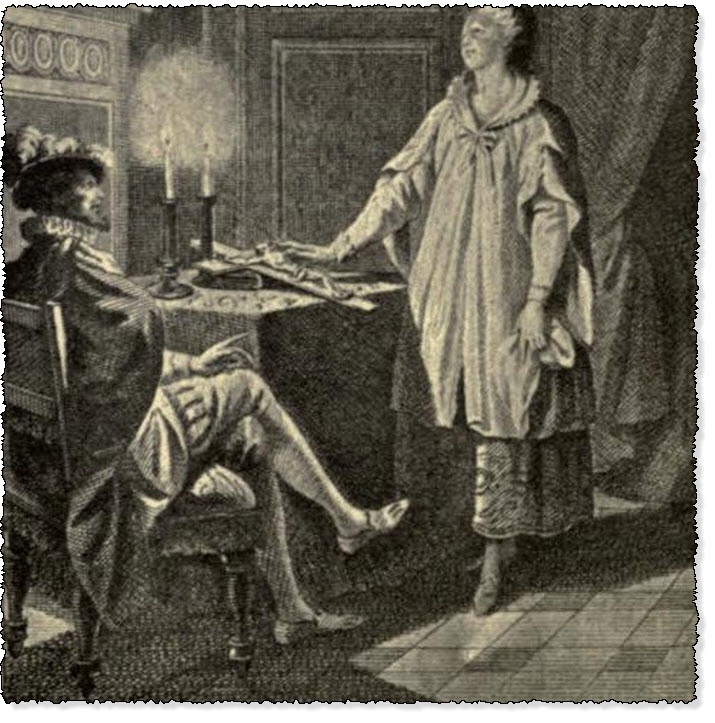

But things are desired all the more for being forbidden, and it was not long before the poor woman had forgotten her husband's threats and her own promises. That very same evening she sent to the gentleman, begging him to visit her at night. But the husband, who was so tormented by jealousy that he could not sleep, and who had heard say that the gentleman visited his wife at night, wrapped himself in a cloak, and taking a valet with him, went to his wife's apartment and knocked at the door. She, not in the least expecting him, got up alone, put on furred slippers and a dressing-gown which were lying close at hand, and finding that the three or four women whom she had with her were asleep, went forth from her room and straight to the door at which she had heard the knocking. On her asking, "Who is there?" she received in answer the name of her lover; but to be still more certain, she opened a little wicket, saying—

"If you be the man you say you are, show me your hand, and I shall recognise it."

And when she touched her husband's hand she knew who it was, and quickly shutting the wicket, cried out—

"Ha, sir! it is your hand."

The husband replied in great wrath—

"Yes; it is the hand that will keep faith with you. Do not fail, therefore, to come when I send for you."

With these words he went away to his own apartment, whilst she, more dead than alive, went back into her room, and cried out aloud to her servant-women, "Get up, my friends; you have slept only too well for me, for thinking to trick you, I have myself been tricked."

With these words she swooned away in the middle of the room. The women rose at her cry, and were so astonished at seeing their mistress stretched upon the floor, as well as at hearing the words, she had uttered, that they were at their wits' end, and sought in haste for remedies to restore her. When she was able to speak, she said to them—

"You see before you, my friends, the most unhappy creature in the world."

And thereupon she went on to tell them the whole adventure, and begged of them to help her, for she counted her life as good as lost.

While they were seeking to comfort her, a valet came with orders that she was to repair to her husband instantly. Thereupon, clinging to two of her women, she began to weep and wail, begging them not to suffer her to go, for she was sure she would be killed. But the valet assured her to the contrary, offering to pledge his life that she should receive no hurt. Seeing that she lacked all means of resistance, she at last threw herself into the servant's arms, and said to him—

"Since it may not be otherwise, you must e'en carry this hapless body to its death."

Half fainting in her distress, she was then at once borne by the valet to his master's apartment. When she reached it, she fell at her husband's feet, and said to him—

"I beseech you, sir, have pity on me, and I swear to you by the faith I owe to God that I will tell you the whole truth."

"'Fore God you shall," he replied, like one beside himself, and forthwith he drove all the servants from the room.

Having always found his wife very devout, he felt sure that she would not dare to forswear herself on the Holy Cross. He therefore sent for a very beautiful crucifix that belonged to him, and when they were alone together, he made her swear upon it that she would return true replies to his questions. Already, however, she had recovered from her first dread of death, and taking courage, she resolved that if she was to die she would make no concealment of the truth, but at the same time would say nothing that might injure the gentleman she loved. Accordingly, having heard all the questions that her husband had to put to her, she replied as follows—

"I have no desire, sir, either to justify myself or to lessen to you the love that I have borne to the gentleman you suspect; for if I did, you could not and you should not believe me. Nevertheless, I desire to tell you the cause of this affection. Know, then, sir, that never did wife love husband more than I loved you, and that from the time I wedded you until I reached my present age, no other passion ever found its way into my heart. You will remember that while I was still a child, my parents wished to marry me to one richer and more highly born than yourself, but they could never gain my consent to this from the moment I had once spoken to you. In spite of all their objections I held fast to you, and gave as little heed to your poverty as to their remonstrances. You cannot but know what treatment I have had at your hands hitherto, and the fashion in which you have loved and honoured me; and this has caused me so much grief and discontent that but for the succour of the lady with whom you placed me, I should have been in despair. But at last, finding myself fully grown and deemed beautiful by all but you, I began to feel the wrong you did me so keenly that the love I had for you changed into hate, and the desire of obeying you into one for revenge. In this despairing condition I was found by a Prince who, being more anxious to obey the King than Love, forsook me just as I was beginning to feel my pangs assuaged by an honourable affection. When the Prince had left me, I lighted upon this present gentleman; and he had no need to entreat me, for his good looks, nobleness, grace, and virtue are well worthy of being sought after and courted by all women of sound understanding. At my instance, not at his own, he has loved me in all virtue, so that never has he sought from me aught that honour might refuse. And although I have but little cause to love you, and so might be absolved from being loyal and true to you, my love of God and of my honour has hitherto sufficed to keep me from doing aught that would call for confession or shame. I will not deny that I went into a closet as often as I could to speak with him, under pretence of going thither to say my prayers, for I have never trusted the conduct of this matter to any one, whether man or woman. Further, I will not deny that when in so secret a place and safe from all suspicion I have kissed him with more goodwill than I kiss you. But as I look to God for mercy, no other familiarity has passed between us; he has never urged me to it, nor has my heart ever desired it; for I was so glad at seeing him that methought the world contained no greater pleasure.

"And now, sir, will you, who are the sole cause of my misfortune, take vengeance for conduct of which you have yourself long since set me an example, with, indeed, this difference, that in your case you thought nought of either honour or conscience; for you know and I know too that the woman you love does not rest content with what God and reason enjoin. And albeit the law of man deals great dishonour to wives who love other men than their husbands, the law of God does not exempt from punishment the husbands who love other women than their wives. And if my offences are to be weighed against yours, you are more to blame than I, for you are a wise and experienced man, and of an age to know and to shun evil, whilst I am young and have no experience of the might and power of love. You have a wife who desires you, honours you, and loves you more than her own life; while I have a husband who avoids me, hates me, and rates me as lightly as he would a servant maid. You are in love with a woman who is already old, of meagre figure, and less fair than I; whilst I love a gentleman younger, handsomer, and more amiable than you. You love the wife of one of the best friends you have in the world, the mistress, moreover, of your King and master, so that you offend against the friendship that is due to the first, and the respect that is due to the second; whereas I am in love with a gentleman whose only tie is his love for me. Judge then fairly which of us two is the more worthy of punishment or pardon: you, a man of wisdom and experience, who through no provocation on my part have acted thus ill not only towards me, but towards the King, to whom you are so greatly indebted; or I, who am young and ignorant, who am slighted and despised by you, and loved by the handsomest and most worshipful gentleman in France, a gentleman whom I have loved in despair of ever being loved by you."

When the husband heard her utter these truths with so fair a countenance, and with such a bold and graceful assurance as clearly testified that she neither dreaded nor deserved any punishment, he was overcome with astonishment, and could find nothing to reply except that a man's honour and a woman's were not the same thing. However, since she swore to him that there had been nothing between herself and her lover but what she had told him, he was not minded to treat her ill, provided she would act so no more, and that they both put away the memory of the past. To this she agreed, and they went to bed in harmony together.

Next morning an old damosel who was in great fear for her mistress's life came to her at her rising, and asked—

"Well, madam, and how do you fare?"

"I would have you know," said her mistress, laughing, "that there is not a better husband than mine, for he believed me on my oath."

And so five or six days passed by.

Meanwhile the husband had such care of his wife that he caused a watch to be kept on her both night and day. But for all his care he could not prevent her from again speaking with her lover in a dark and suspicious place. However, she contrived matters with such secrecy that no one, whether man or woman, could ever learn the truth, though a rumour was started by some serving-man about a gentleman and a lady whom he had found in a stable underneath the rooms belonging to the mistress of the lady in question. At this her husband's suspicions were so great that he resolved to slay the gentleman, and gathered together a large number of his relations and friends to kill him if he was anywhere to be found. But the chief among his kinsmen was so great a friend of the gentleman whom they sought, that instead of surprising him he gave him warning of all that was being contrived against him, for which reason the other, being greatly liked by the whole Court, was always so well attended that he had no fear of his enemy's power, and could not be taken unawares and attacked.

However, he betook himself to a church to meet his lady's mistress, who had heard nothing of all that had passed, for the lovers had never spoken together in her presence. But the gentleman now informed her of the suspicion and ill-will borne him by the lady's husband, and told her that although he was guiltless he had nevertheless resolved to go on a long journey in order to check the rumours, which were beginning greatly to increase. The Princess, his lady's mistress, was much astonished on hearing this tale, and protested that the husband was much in the wrong to suspect so virtuous a wife, and one in whom she had ever found all worth and honour. Nevertheless, considering the husband's authority, and in order to quell these evil reports, she advised him to absent himself for a time, assuring him that for her part she would never believe such foolish suspicions.

Both the gentleman and the lady, who was present, were well pleased at thus preserving the favour and good opinion of the Princess, who further advised the gentleman to speak with the husband before his departure. He did as he was counselled, and meeting with the husband in a gallery close to the King's apartment, he assumed a bold countenance, and said to him with all the respect due to one of high rank—

"All my life, sir, I have desired to do you service, and my only reward is to hear that last evening you lay in wait to kill me. I pray you, sir, reflect that while you have more authority and power than I have, I am nevertheless a gentleman even as you are. It would be grievous to me to lose my life for naught. I pray you also reflect that you have a wife of great virtue, and if any man pretend the contrary I will tell him that he has foully lied. For my part, I can think of nothing that I have done to cause you to wish me ill. If, therefore, it please you, I will remain your faithful servant; if not, I am that of the King, and with that I may well be content."

The husband replied that he had in truth somewhat suspected him, but he deemed him so gallant a man that he would rather have his friendship than his enmity; and bidding him farewell, cap in hand, he embraced him like a dear friend. You may imagine what was said by those who, the evening before, had been charged to kill the gentleman, when they beheld such tokens of respect and friendship. And many and diverse were the remarks that each one made.

In this manner the gentleman departed, and as he had far less money than good looks, his mistress delivered to him a ring that her husband had given her of the value of three thousand crowns; and this he pledged for fifteen hundred.

Some time after he was gone, the husband came to the Princess, his wife's mistress, and prayed her to grant his wife leave to go and dwell for a while with one of his sisters. This the Princess thought very strange, and so begged him to tell her the reasons of his request, that he told her part of them, but not all. When the young lady had taken leave of her mistress and of the whole Court without shedding any tears or showing the least sign of grief, she departed on her journey to the place whither her husband desired her to go, travelling under the care of a gentleman who had been charged to guard her closely, and above all not to suffer her to speak on the road to her suspected lover.

Heptameron Story 15

She knew of these instructions, and every day was wont to cause false alarms, scoffing at her custodians and their lack of care. Thus one day, on leaving her lodging, she fell in with a Grey Friar on horseback, with whom, being herself on her palfrey, she talked on the road the whole time from the dinner to the supper hour. And when she was a quarter of a league from the place where she was to lodge that night, she said to him—

"Here, father, are two crowns which I give you for the consolation you have afforded me this afternoon. They are wrapped in paper, for I well know that you would not venture to touch them. (2) And I beg you to leave the road as soon as you have parted from me, and to take care that you are not seen by those who are with me. I say this for your own welfare, and because I feel myself beholden to you."

The friar, well pleased with the two crowns, set off across the fields at full gallop; and when he was some distance away the lady said aloud to her attendants—

"You may well deem yourselves good servants and diligent guards. He as to whom you were to be so careful has been speaking to me the whole day, and you have suffered him to do so. Your good master, who puts so much trust in you, should give you the stick rather than give you wages."

When the gentleman who had charge of her heard these words he was so angry that he could not reply, but calling two others to him, set spurs to his horse, and rode so hard that he at last reached the friar, who on perceiving his pursuers had fled as fast as he could. However, the poor fellow was caught, being less well mounted than they were. He was quite ignorant of what it all meant, and cried them mercy, taking off his hood in order that he might entreat them with bareheaded humility. Thereupon they realised that he was not the man whom they sought, and that their mistress had been mocking them. And this she did with even better effect upon their return to her.

"You are fitting fellows," said she, "to receive ladies in your charge. You suffer them to talk to any stranger, and then, believing whatever they may say, you go and insult the ministers of God."

After all these jests they arrived at the place that her husband had commanded, and here her two sisters-in-law, with the husband of one of them, kept her in great subjection.

In the meanwhile her husband had heard how his ring had been pledged for fifteen hundred crowns, whereat he was exceedingly wrathful, and in order to save his wife's honour and to get back the ring, he bade his sisters tell her to redeem it, he himself paying the fifteen hundred crowns.

She cared nought for the ring since her lover had the money, but she wrote to him saying that she was compelled by her husband to redeem it, and in order that he might not suppose she was doing this through any lessening of her affection, she sent him a diamond which her mistress had given, her, and which she liked better than any ring she had.

Thereupon the gentleman forwarded her the merchant's bond right willingly; deeming himself fortunate in having fifteen hundred crowns and a diamond, (3) and at being still assured of his lady's favour. However, as long as the husband lived, he had no means of communing with her save by writing.

When the husband died, expecting to find her still what she had promised him to be, he came in all haste to ask her in marriage; but he found that his long absence had gained him a rival who was loved better than himself. His sorrow at this was so great that he henceforth shunned the companionship of ladies and sought out scenes of danger, and so at last died in as high repute as any young man could have. (4)

"In this tale, ladies, I have tried, without sparing our own sex, to show husbands that wives of spirit yield rather to vengeful wrath than to the sweetness of love. The lady of whom I have told you withstood the latter for a great while, but in the end succumbed to despair. Nevertheless, no woman of virtue should yield as she did, for, happen what may, no excuse can be found for doing wrong. The greater the temptations, the more virtuous should one show oneself, by resisting and overcoming evil with good, instead of returning evil for evil; and this all the more because the evil we think to do to another often recoils upon ourselves. Happy are those women who display the heavenly virtues of chastity, gentleness, meekness, and long-suffering."

"It seems to me, Longarine," said Hircan, "that the lady of whom you have spoken was impelled by resentment rather than by love; for had she loved the gentleman as greatly as she appeared to do, she would not have forsaken him for another. She may therefore be called resentful, vindictive, obstinate, and fickle."

"It is all very well for you to talk in that way," said Ennasuite, "but you do not know the heartbreak of loving without return."

"It is true," said Hircan, "that I have had but little experience in that way. If I am shown the slightest disfavour, I forthwith forego lady and love together."

"That," said Parlamente, "is well enough for you who love only your own pleasure; but a virtuous wife cannot thus forsake her husband."

"Yet," returned Simontault, "the lady in the story forgot for a while that she was a woman. No man could have taken a more signal revenge."

"It does not follow," said Oisille, "because one woman lacks discretion that all the rest are the same."

"Nevertheless," said Saffredent, "you are all women, as any one would find who looked carefully, despite all the fine clothes you may wear."

"If we were to listen to you," said Nomerlide, "we should spend the day in disputes. For my part, I am so impatient to hear another tale, that I beg Longarine to give some one her vote."

Longarine looked at Geburon and said:—

"If you know anything about a virtuous woman, I pray you set it forth."

"Since I am to do what I can," said Geburon, "I will tell you a tale of something that happened in the city of Milan."

Footnotes:

- The incidents referred to in this story must have occurred between 1515 and 1543, during the reign of Francis I.—L.

- The Grey Friars belonging to a mendicant order were prohibited from demanding or accepting money; it was only allowable for them to receive gifts in kind, mainly edible produce. It was for this reason that the lady gave the friar the two crowns wrapped in paper, knowing that he ought not to touch the coins.—M. See also vol. i. p. 98, note 3.

- The gentleman deemed it only natural that the woman he honoured with his love should present him with money. In the seventeenth century similar opinions were held, if one may judge by some passages in Dancourt's comedies, and by the presents which the Duchess of Cleveland made to Henry Jerrayn and John Churchill, afterwards Duke of Marlborough, as chronicled in the Memoirs of the Count de Gramont.—M.

- Brant�me tells a somewhat similar tale to this in his Vies des Dames Galantes (Dis. I.): "I knew," he writes, "two ladies of the Court, sisters-in-law to one another, one of whom was married to a courtier, high in favour and very skilful, but who did not make as much account of his wife as by reason of her birth he should have done, for he spoke to her in public as he might have spoken to a savage, and treated her most harshly. She patiently endured this for some time, until indeed her husband lost some of his credit, when, watching for and taking the opportunity, she quickly repaid him for all the disdain that he had shown her. And her sister-in-law imitated her and did likewise; for having been married when of a young and tender age, her husband made no more account of her than if she had been a little girl.... But she, advancing in years, feeling her heart beat and becoming conscious of her beauty, paid him back in the same coin, and made him a present of a fine pair of horns, by way of interest for the past"—Lalanne's OEuvres de Brant�me, vol. ix. p. 157.—L.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.