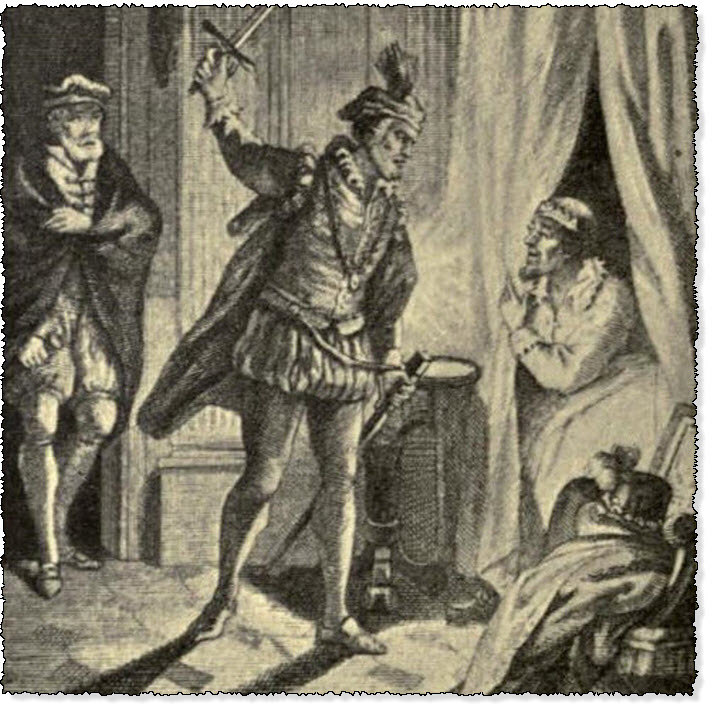

The Gentleman Attacking The Duke

Day 2 of the Heptameron - Tale 12

Summary of the Second Tale Told on the Second Day of the Heptameron

Tale 12 of the Heptameron

Ten years ago there reigned in the city of Florence a Duke of the house of Medici who had married the Emperor's natural daughter, Margaret. (2) She was still so young that the marriage could not be lawfully consummated, and, waiting till she should be of a riper age, the Duke treated her with great gentleness, and to spare her, made love to various ladies of the city, whom he was wont to visit at night, whilst his wife was sleeping.

Among these there was one very beautiful, discreet, and honourable lady, sister to a gentleman whom the Duke loved even as himself, and to whom he gave such authority in his household that his orders were feared and obeyed equally with the Duke's own. And moreover the Duke had no secrets that he did not share with this gentleman, so that the latter might have been called his second-self. (3)

Finding the gentleman's sister to be a lady of such exemplary virtue that he was unable to declare his passion to her, though he sought all possible opportunities for doing so, the Duke at last came to his favourite and said to him—

"If there were anything in this world, my friend, that I might be unwilling to do for you, I should hesitate to tell you what is in my mind, and still more to beg your assistance. But such is the affection I bear you that had I wife, mother, or daughter who could avail to save your life, I would sacrifice them rather than allow you to die in torment. I believe that your love for me is the counterpart of mine for you, and that if I, who am your master, bear you so much affection, you, on your part, can have no less for me. I will therefore tell you a secret, the keeping of which has brought me to the condition you see. I have no hope of any improvement except it be through death or else the service which you are in a position to render me."

On hearing these words from the Duke, and seeing his face unfeignedly bathed in tears, the gentleman felt such great pity for him that he said—

"Sir, I am your creature: all the wealth and honour that I am possessed of in this world come from you. You may speak to me as to your own soul, in the certainty that all that it be in my power to do is at your command."

Thereupon the Duke began to tell him of the love he bore his sister, a love so deep and strong that he feared he could not live much longer unless, by the gentleman's help, he succeeded in satisfying his desire. He was well aware that neither prayers nor presents would be of any avail with the lady, wherefore he begged the gentleman—if he cared for his master's life as much as he, his master, cared for his—to devise some means of procuring him the good fortune which, without such assistance, he could never hope to obtain.

The brother, who loved his sister and the honour of his house far more than the Duke's pleasure, endeavoured to remonstrate with him, entreating that he might be employed for any other purpose save the cruel task of soliciting the dishonour of his own kin, and declaring that the rendering of such a service was contrary alike to his inclinations and his honour.

Inflamed with excessive wrath, the Duke raised his hand to his mouth and bit his nails.

"Well," said he in a fury, "since I find that you have no friendship for me, I know what I have to do."

The gentleman, who was acquainted with his master's cruelty, felt afraid, and answered—

"My lord, since such is your pleasure, I will speak to her, and tell you her reply."

"If you show concern for my life, I shall show it for yours," replied the Duke, and thereupon he went away.

The gentleman well understood the meaning of these words, and spent a day or two without seeing the Duke, considering what he should do. On the one hand he was confronted by the duty he owed his master, and the wealth and honours he had received from him; on the other by the honour of his house, and the fair fame and chastity of his sister. He well knew that she would never submit to such infamy unless through his own treachery she were overcome by violence, so unnatural a deed that if it were committed he and his kindred would be disgraced for ever. In this dilemma he decided that he would sooner die than so ill use his sister, who was one of the noblest women in all Italy, and ought rather to deliver his country of this tyrant who, abusing his power, sought to cast such a slur upon his family; for he felt sure that if the Duke were suffered to live, neither his own life nor the lives of his kindred would be safe. So without speaking of the matter to his sister or to any living creature, he determined to save his life and vindicate his honour at one and the same time. Accordingly, when a couple of days had gone by, he went to the Duke and told him that with infinite difficulty he had so wrought upon his sister that she had at last consented to do his will, provided that the matter were kept secret, and none but he, her brother, knew of it.

The Duke, who was longing for these tidings, readily believed them, and embracing the ambassador, promised him anything that he might ask. He begged him to put his scheme quickly into execution, and they agreed together upon the time when this should be done. The Duke was in great joy, as may well be imagined; and on the arrival of that wished-for night when he hoped to vanquish her whom he had deemed invincible, he retired early, accompanied only by the lady's brother, and failed not to attire himself in a perfumed shirt and head-gear. Then, when every one was gone to rest, he went with the gentleman to the lady's abode, where he was conducted into a well-appointed apartment.

Having undressed him and put him to bed, the gentleman said—

"My lord, I will now go and fetch you one who will assuredly not enter this room without blushing; but I hope that before morning she will have lost all fear of you."

Leaving the Duke, he then went to his own room, where he found one of his servants, to whom he said—

"Are you brave enough to follow me to a place where I desire to avenge myself upon my greatest living enemy?"

The other, who was ignorant of his master's purpose, replied—

"Yes, sir, though it were the Duke himself."

Thereupon the gentleman led him away in such haste as to leave him no time to take any weapon except a poignard that he was wearing.

The Duke, on hearing the gentleman coming back again, thought that he was bringing the loved one with him, and, opening his eyes, drew back the curtains in order to see and welcome the joy for which he had so long been waiting. But instead of seeing her who, so he hoped, was to preserve his life, he beheld something intended to take his life away, that is, a naked sword which the gentleman had drawn, and with which he smote the Duke. The latter was wearing nothing but his shirt, and lacked weapons, though not courage, for sitting up in the bed he seized the gentleman round the body, saying—

"Is this the way you keep your promise?"

Then, armed as he was only with his teeth and nails, he bit the gentleman's thumb, and wrestled with him so stoutly that they both fell down beside the bed.

The gentleman, not feeling altogether confident, called to his servant, who, finding the Duke and his master so closely twined together that he could not tell the one from the other, dragged them both by the feet into the middle of the room, and then tried to cut the Duke's throat with his poignard. The Duke defended himself until he was so exhausted through loss of blood that he could do no more, whereupon the gentleman and his servant lifted him upon the bed and finished him with their daggers. They then drew the curtain and went away, leaving the dead body shut up in the room.

Having vanquished his great enemy, by whose death he hoped to free his country, the gentleman reflected that his work would be incomplete unless he treated five or six of the Duke's kindred in the same fashion. The servant, however, who was neither a dare-devil nor a fool, said to him—

"I think, sir, that you have done enough for the present, and that it would be better to think of saving your own life than of taking the lives of others, for should we be as long in making away with each of them as we were in the case of the Duke, daylight would overtake our enterprise before we could complete it, even should we find our enemies unarmed."

Cowed by his guilty conscience, the gentleman followed the advice of his servant, and taking him alone with him, repaired to a Bishop (4) whose office it was to have the city gates opened, and to give orders to the guard-posts.

"I have," said the gentleman to the Bishop, "this evening received tidings that one of my brothers is at the point of death. I have just asked leave of the Duke to go to him, and he has granted it me; and I beg you to send orders that the guards may furnish me with two good horses, and that the gatekeeper may let me through."

The Bishop, who regarded the gentleman's request in the same light as an order from his master the Duke, forthwith gave him a note, by means of which the gate was opened for him, and horses supplied to him as he had requested; but instead of going to see his brother he betook himself straight to Venice, where he had himself cured of the bites that he had received from the Duke, and then passed over into Turkey. (5)

In the morning, finding that their master delayed his return so long, all the Duke's servants suspected, rightly enough, that he had gone to see some lady; but at last, as he still failed to return, they began seeking him on all sides. The poor Duchess, who was beginning to love him dearly, was sorely distressed on learning that he could not be found; and as the gentleman to whom he bore so much affection was likewise nowhere to be seen, some went to his house in quest of him. They found blood on the threshold of the gentleman's room, which they entered, but he was not there, nor could any servant or other person give any tidings of him. Following the blood-stains, however, the Duke's servants came at last to the room in which their master lay. The door of it was locked, but this they soon broke open, and on seeing the floor covered with blood they drew back the bed-curtain, and found the unhappy Duke's body lying in the bed, sleeping the sleep from which one cannot awaken.

You may imagine the mourning of these poor servants as they carried the body to the palace, whither came the Bishop, who told them how the gentleman had departed with all speed during the night under pretence of going to see his brother. And by this it was clearly shown that it was he who had committed the murder. And it was further proved that his poor sister had known nothing whatever of the matter. For her part, albeit she was astounded by what had happened, she could but love her brother the more, seeing that he had not shrunk from risking his life in order to save her from so cruel a tyrant. And so honourable and virtuous was the life that she continued leading, that although she was reduced to poverty by the confiscation of the family property, both she and her sister found as honourable and wealthy husbands as there were in all Italy, and lived ever afterwards in high and good repute.

"This, ladies, is a story that should make you dread that little god who delights in tormenting Prince and peasant, strong and weak, and so far blinds them that they lose all thought of God and conscience, and even of their own lives. And greatly should Princes and those in authority fear to offend such as are less than they; for there is no man but can wreak injury when it pleases God to take vengeance on a sinner, nor any man so great that he can do hurt to one who is in God's care."

This tale was commended by all in the company, (6) but it gave rise to different opinions among them, for whilst some maintained that the gentleman had done his duty in saving his own life and his sister's honour, as well as in ridding his country of such a tyrant, others denied this, and said it was rank ingratitude to slay one who had bestowed on him such wealth and station. The ladies declared that the gentleman was a good brother and a worthy citizen; the men, on the contrary, that he was a treacherous and wicked servant.

And pleasant was it to hear the reasons which were brought forward on both sides; but the ladies, as is their wont, spoke as much from passion as from judgment, saying that the Duke was so well worthy of death that he who struck him down was a happy man indeed.

Then Dagoucin, seeing what a controversy he had set on foot, said to them—

"In God's name, ladies, do not quarrel about a thing that is past and gone. Take care rather that your own charms do not occasion more cruel murders than the one which I have related."

"'La belle Dame sans Mercy,'" (7) replied Parlamente, "has taught us to say that but few die of so pleasing an ailment."

"Would to God, madam," answered Dagoucin, "that all the ladies in this company knew how false that saying is. I think they would then scarcely wish to be called pitiless, or to imitate that unbelieving beauty who suffered a worthy lover to die for lack of a gracious answer to his suit."

"So," said Parlamente, "you would have us risk honour and conscience to save the life of a man who says he loves us."

"That is not my meaning," replied Dagoucin, "for he who loves with a perfect love would be even more afraid of hurting his lady's honour than would she herself. I therefore think that an honourable and graceful response, such as is called for by perfect and seemly love, must tend to the increase of honour and the satisfaction of conscience, for no true lover could seek the contrary."

"That is always the end of your speeches," said Ennasuite; "they begin with honour and end with the contrary. However, if all the gentlemen present will tell the truth of the matter, I am ready to believe them on their oaths."

Heptameron Story 12

Hircan swore that for his own part he had never loved any woman but his own wife, and even with her had no desire to be guilty of any gross offence against God.

Simontault declared the same, and added that he had often wished all women were froward excepting his own wife.

"Truly," said Geburon to him, "you deserve that your wife should be what you would have the others. For my own part, I can swear to you that I once loved a woman so dearly that I would rather have died than have led her to do anything that might have diminished my esteem for her. My love for her was so founded upon her virtues, that for no advantage that I might have had of her would I have seen them blemished."

At this Saffredent burst out laughing.

"Geburon," he said, "I thought that your wife's affection and your own good sense would have guarded you from the danger of falling in love elsewhere, but I see that I was mistaken, for you still use the very phrases with which we are wont to beguile the most subtle of women, and to obtain a hearing from the most discreet. For who would close her ears against us when we begin our discourse by talking of honour and virtue? (8) But if we were to show them our hearts just as they are, there is many a man now welcome among the ladies whom they would reckon of but little account. But we hide the devil in our natures under the most angelic form we can devise, and in this disguise receive many favours before we are found out. And perhaps we lead the ladies' hearts so far forward, that when they come upon vice while believing themselves on the high road to virtue, they have neither opportunity nor ability to draw back again."

"Truly," said Geburon, "I thought you a different man than your words would show you to be, and fancied that virtue was more pleasing to you than pleasure."

"What!" said Saffredent. "Is there any virtue greater than that of loving in the way that God commands? It seems to me that it is much better to love one woman as a woman than to adore a number of women as though they were so many idols. For my part, I am firmly of opinion that use is better than abuse."

The ladies, however, all sided with Geburon, and would not allow Saffredent to continue, whereupon he said—

"I am well content to say no more on this subject of love, for I have been so badly treated with regard to it that I will never return to it again."

"It is your own maliciousness," said Longarine, "that has occasioned your bad treatment; for what virtuous woman would have you for a lover after what you have told us?"

"Those who did not consider me unwelcome," answered Saffredent, "would not care to exchange their virtue for yours. But let us say no more about it, that my anger may offend neither myself nor others. Let us see to whom Dagoucin will give his vote."

"I give it to Parlamente," said Dagoucin, "for I believe that she must know better than any one else the nature of honourable and perfect love."

"Since I have been chosen to tell the third tale," said Parlamente, "I will tell you something that happened to a lady who has always been one of my best friends, and whose thoughts have never been hidden from me."

Footnotes:

- The basis of this story is historical. The event here described—one of the most famous in the annals of Florence—furnished Alfred de Musset with the subject of his play Lorenzaccio, and served as the foundation of The Traitor, considered to be Shirley's highest achievement as a dramatic poet. As Queen Margaret's narrative contains various errors of fact, Sismondi's account of the affair, as borrowed by him from the best Italian historians, is given in the Appendix, C—Eu.

- The Duke here referred to was Alexander de' Medici, first Duke of Florence, in which city he was born in 1510. His mother, a slave named Anna, was the wife of a Florentine coachman, but Lorenzo II. de' Medici, one of this woman's lovers, acknowledged him as his offspring, though, according to some accounts, his real father was one of the popes, Clement VII. or Julius II. After the Emperor Charles V. had made himself master of Florence in 1530, he confided the governorship of the city to Alexander, upon whom he bestowed the title of Duke. Two years later Alexander threw off the imperial control, and soon afterwards embarked on a career of debauchery and crime. In 1536, Charles V., being desirous of obtaining the support of Florence against France, treated with Alexander, and gave him the hand of his illegitimate daughter, Margaret. The latter—whose mother was Margaret van Gheenst, a Flemish damsel of noble birth—was at that time barely fourteen, having been born at Brussels in 1522. The Queen of Navarre's statements concerning the youthfulness of the Duchess are thus corroborated by fact. After the death of Alexander de' Medici, his widow was married to Octavius Farnese, Duke of Parma, who was then only twelve years old, but by whom she eventually became the mother of the celebrated Alexander Farnese. Margaret of Austria occupies a prominent place in the history of the Netherlands, which she governed during a lengthy period for her brother Philip II. She died in retirement at Ortonna in Italy in 1586.—L. and Ed.

- The gentleman here mentioned was the Duke's cousin, Lorenzo di Pier-Francesco de' Medici, commonly called Lorenzino on account of his short stature. He was born at Florence in 1514, and, being the eldest member of the junior branch of the Medici family, it had been decided by the Emperor Charles V. that he should succeed to the Dukedom of Florence, if Alexander died without issue. Lorenzino cultivated letters, and is said to have possessed considerable wit, but, on the other hand, instead of being a high-minded man, as Queen Margaret pictures him, he was a thorough profligate, and willingly lent a hand in Alexander's scandalous amours. The heroine of this story is erroneously described as Lorenzino's sister; in point of fact she was his aunt, Catherine Ginori. See Appendix, C.— Ed.

- Probably Cardinal Cybo, Alexander's chief minister, who according to Sismondi, was the first to discover the murder.—Ed.

- On leaving Florence, Lorenzo repaired first to Bologna and then to Venice, where he informed Philip Strozzi of how he had rid his country of the tyrant. After embracing him in a transport, and calling him the Tuscan Brutus, Strozzi asked the murderer's sisters, Laudamina and Magdalen de' Medici, in marriage for his own sons, Peter and Robert. From Venice Lorenzino issued a mémoire justificatif, full of quibbles and paradoxes, in which he tried to explain his lack of energy after the murder by the indifference shown by the Florentines. He took no part in the various enterprises directed against Cosmo de' Medici, who had succeeded Alexander at Florence. Indeed his chief concern was for his own safety, which was threatened alike by Cosmo and the Emperor Charles V., and to escape their emissaries he proceeded to Turkey, and thence to France, ultimately returning to Venice, where, despite all his precautions against danger, he was assassinated in 1547, together with his uncle, Soderini, by some spadassins in the pay of Cosmo I.—Ed.

- In MS. No. 1520 (Bib. Nat.) this sentence begins: "The tale was attentively listened to by all," &c.—L.

- La belle Dame sans Merci (The Pitiless Beauty) is one of Alain Chartier's best known poems. It is written in the form of a dialogue between a lady and her lover: the former having obstinately refused to take compassion on the sufferings of her admirer, the latter is said to have died of despair. The lines alluded to by Margaret are spoken by the lady, and are to the following effect—"So graceful a malady seldom puts men to death; yet the sooner to obtain comfort, it is fitting one should say that it did. Some complain and worry greatly who have not really felt the most bitter affliction; and if indeed Love doth cause such great torment, surely it were better there should be but one sufferer rather than two." The poem, as here quoted, will be found in André Duchesne's edition of the OEuvres de Maistre Alain Chartier, Paris, 1617, p. 502.—L.

- This sentence is borrowed from MS. No. 1520 (Bib. Nat.)— L.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.