The Heptameron - Day 1 - Tale 8

The Heptameron - Day 1 - Tale 8

Summary of the Eighth Tale Told on the First Day of the Heptameron

Tale 8 of the Heptameron

In the county of Alletz (2) there lived a man named Bornet, who being married to an upright and virtuous wife, had great regard for her honour and reputation, as I believe is the case with all the husbands here present in respect to their own wives. But although he desired that she should be true to him, he was not willing that the same law should apply to both, for he fell in love with his maid-servant, from whom he had nothing to gain save the pleasure afforded by a diversity of viands.

Now he had a neighbour of the same condition as his own, named Sandras, a tabourer (3) and tailor by trade, and there was such friendship between them that, excepting Bornet's wife, they had all things in common. It thus happened that Bornet told his friend of the enterprise he had in hand against the maid-servant; and Sandras not only approved of it, but gave all the assistance he could to further its accomplishment, hoping that he himself might share in the spoil.

The maid-servant, however, was loth to consent, and finding herself hard pressed, she went to her mistress, told her of the matter, and begged leave to go home to her kinsfolk, since she could no longer endure to live in such torment. Her mistress, who had great love for her husband and had often suspected him, was well pleased to have him thus at a disadvantage, and to be able to show that she had doubted him justly. Accordingly, she said to the servant—

"Remain, my girl, but lead my husband on by degrees, and at last make an appointment to lie with him in my closet. Do not fail to tell me on what night he is to come, and see that no one knows anything about it."

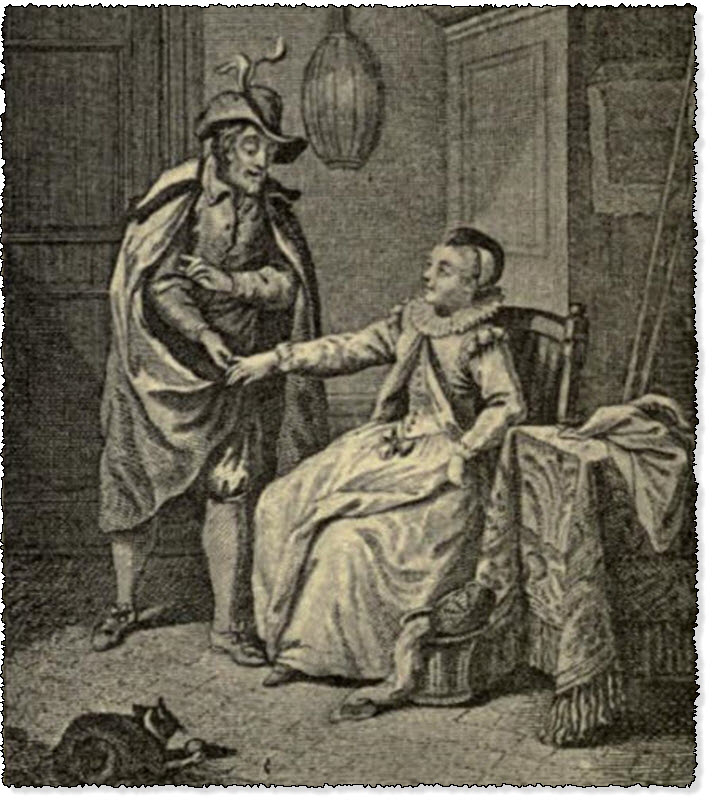

The maid-servant did all that her mistress had commanded her, and her master in great content went to tell the good news to his friend. The latter then begged that, since he had been concerned in the business, he might have part in the result. This was promised him, and, when the appointed hour was come, the master went to lie, as he thought, with the maid-servant; but his wife, yielding up the authority of commanding for the pleasure of obeying, had put herself in the servant's place, and she received him, not in the manner of a wife, but after the fashion of a frightened maid. This she did so well that her husband suspected nothing.

I cannot tell you which of the two was the better pleased, he at the thought that he was deceiving his wife, or she at really deceiving her husband. When he had remained with her, not as long as he wished, but according to his powers, which were those of a man who had long been married, he went out of doors, found his friend, who was much younger and lustier than himself, and told him gleefully that he had never met with better fortune. "You know what you promised me," said his friend to him.

"Go quickly then," replied the husband, "for she may get up, or my wife have need of her."

The friend went off and found the supposed maid-servant, who, thinking her husband had returned, denied him nothing that he asked of her, or rather took, for he durst not speak. He remained with her much longer than her husband had done, whereat she was greatly astonished, for she had not been wont to pass such nights. Nevertheless, she endured it all with patience, comforting herself with the thought of what she would say to him on the morrow, and of the ridicule that she would cast upon him.

Towards daybreak the man rose from beside her, and toying with her as he was going away, snatched from her finger the ring with which her husband had espoused her, and which the women of that part of the country guard with great superstition. She who keeps it till her death is held in high honour, while she who chances to lose it, is thought lightly of as a person who has given her faith to some other than her husband.

The wife, however, was very glad to have it taken, thinking it would be a sure proof of how she had deceived her husband. When the friend returned, the husband asked him how he had fared. He replied that he was of the same opinion as himself, and that he would have remained longer had he not feared to be surprised by daybreak. Then they both went to the friend's house to take as long a rest as they could. In the morning, while they were dressing, the husband perceived the ring that his friend had on his finger, and saw that it was exactly like the one he had given to his wife at their marriage. He thereupon asked his friend from whom he had received the ring, and when he heard he had snatched it from the servant's finger, he was confounded and began to strike his head against the wall, saying—"Ah! good Lord! have I made myself a cuckold without my wife knowing anything about it?"

Heptameron Story 8

"Perhaps," said his friend in order to comfort him, "your wife gives her ring into the maid's keeping at night-time."

The husband made no reply, but took himself home, where he found his wife fairer, more gaily dressed, and merrier than usual, like one who rejoiced at having saved her maid's conscience, and tested her husband to the full, at no greater cost than a night's sleep. Seeing her so cheerful, the husband said to himself—

"If she knew of my adventure she would not show me such a pleasant countenance."

Then, whilst speaking to her of various matters, he took her by the hand, and on noticing that she no longer wore the ring, which she had never been accustomed to remove from her finger, he was quite overcome.

"What have you done with your ring?" he asked her in a trembling voice.

She, well pleased that he gave her an opportunity to say what she desired, replied—

"O wickedest of men! From whom do you imagine you took it? You thought it was from my maid-servant, for love of whom you expended more than twice as much of your substance as you ever did for me. The first time you came to bed I thought you as much in love as it was possible to be; but after you had gone out and were come back again, you seemed to be a very devil. Wretch! think how blind you must have been to bestow such praises on my person and lustiness, which you have long enjoyed without holding them in any great esteem. 'Twas, therefore, not the maid-servant's beauty that made the pleasure so delightful to you, but the grievous sin of lust which so consumes your heart and so clouds your reason that in the frenzy of your love for the servant you would, I believe, have taken a she-goat in a nightcap for a comely girl! Now, husband, it is time to amend your life, and, knowing me to be your wife, and an honest woman, to be as content with me as you were when you took me for a pitiful strumpet. What I did was to turn you from your evil ways, so that in your old age we might live together in true love and repose of conscience. If you purpose to continue your past life, I had rather be severed from you than daily see before my eyes the ruin of your soul, body, and estate. But if you will acknowledge the evil of your ways, and resolve to live in fear of God and obedience to His commandments, I will forget all your past sins, as I trust God will forget my ingratitude in not loving Him as I ought to do."

If ever man was reduced to despair it was this unhappy husband. Not only had he abandoned this sensible, fair, and chaste wife for a woman who did not love him, but, worse than this, he had without her knowledge made her a strumpet by causing another man to participate in the leasure which should have been for himself alone; and thus he had made himself horns of everlasting derision. However, seeing his wife in such wrath by reason of the love he had borne his maid-servant, he took care not to tell her of the evil trick that he had played her; and entreating her forgiveness, with promises of full amendment of his former evil life, he gave her back the ring which he had recovered from his friend. He entreated the latter not to reveal his shame; but, as what is whispered in the ear is always proclaimed from the housetop, the truth, after a time, became known, and men called him cuckold without imputing any shame to his wife.

"It seems to me, ladies, that if all those who have committed like offences against their wives were to be punished in the same way, Hircan and Saffredent would have great cause for fear."

"Why, Longarine," said Saffredent, "are none in the company married save Hircan and I?"

"Yes, indeed there are others," she replied, "but none who would play a similar trick."

"Whence did you learn," asked Saffredent, "that we ever solicited our wives' maid-servants?"

"If the ladies who are in question," said Longarine, "were willing to speak the truth, we should certainly hear of maid-servants dismissed without notice."

"Truly," said Geburon, "you are a most worthy lady! You promised to make the company laugh, and yet are angering these two poor gentlemen."

"Tis all one," said Longarine: "so long as they do not draw their swords, their anger will only serve to increase our laughter."

"A pretty business indeed!" said Hircan. "Why, if our wives chose to believe this lady, she would embroil the seemliest household in the company."

"I am well aware before whom I speak," said Longarine. "Your wives are so sensible and bear you so much love, that if you were to give them horns as big as those of a deer, they would nevertheless try to persuade themselves and every one else that they were chaplets of roses."

At this the company, and even those concerned, laughed so heartily that their talk came to an end. However, Dagoucin, who had not yet uttered a word, could not help saying—

"Men are very unreasonable when, having enough to content themselves with at home, they go in search of something else. I have often seen people who, not content with sufficiency, have aimed at bettering themselves, and have fallen into a worse position than they were in before. Such persons receive no pity, for fickleness is always blamed."

"But what say you to those who have not found their other half?" asked Simontault. "Do you call it fickleness to seek it wherever it may be found?"

"Since it is impossible," said Dagoucin, "for a man to know the whereabouts of that other half with whom there would be such perfect union that one would not differ from the other, he should remain steadfast wherever love has attached him. And whatsoever may happen, he should change neither in heart nor in desire. If she whom you love be the image of yourself, and there be but one will between you, it is yourself you love, and not her."

"Dagoucin," said Hircan, "you are falling into error. You speak as though we should love women without being loved in return."

"Hircan," replied Dagoucin, "I hold that if our love be based on the beauty, grace, love, and favour of a woman, and our purpose be pleasure, honour, or profit, such love cannot long endure; for when the foundation on which it rests is gone, the love itself departs from us. But I am firmly of opinion that he who loves with no other end or desire than to love well, will sooner yield up his soul in death than suffer his great love to leave his heart."

"In faith," said Simontault, "I do not believe that you have ever been in love. If you had felt the flame like other men, you would not now be picturing to us Plato's Republic, which may be described in writing but not be put into practice."

"Nay, I have been in love," said Dagoucin, "and am so still, and shall continue so as long as I live. But I am in such fear lest the manifestation of this love should impair its perfection, that I shrink from declaring it even to her from whom I would fain have the like affection. I dare not even think of it lest my eyes should reveal it, for the more I keep my flame secret and hidden, the more does my pleasure increase at knowing that my love is perfect."

"For all that," said Geburon, "I believe that you would willingly have love in return."

"I do not deny it," said Dagoucin, "but even were I beloved as much as I love, my love would not be increased any more than it could be lessened, were it not returned with equal warmth."

Upon this Parlamente, who suspected this fantasy of Dagoucin's, said—

"Take care, Dagoucin; I have known others besides you who preferred to die rather than speak."

"Such persons, madam;" said Dagoucin, "I deem very happy."

"Doubtless," said Saffredent, "and worthy of a place among the innocents of whom the Church sings:

'Non loquendo sed moriendo confessi sunt.' (4)

I have heard much of such timid lovers, but I have never yet seen one die. And since I myself have escaped death after all the troubles I have borne, I do not think that any one can die of love."

"Ah, Saffredent!" said Dagoucin, "how do you expect to be loved since those who are of your opinion never die? Yet have I known a goodly number who have died of no other ailment than perfect love."

"Since you know such stories," said Longarine, "I give you my vote to tell us a pleasant one, which shall be the ninth of to-day."

"To the end," said Dagoucin, "that signs and miracles may lead you to put faith in what I have said, I will relate to you something which happened less than three years ago."

Footnotes:

- For a list of tales similar to this one, see post, Appendix A.

- Alletz, now Alais, a town of Lower Languedoc (department of the Gard), lies on the Gardon, at the foot of the Cevennes mountains. It was formerly a county, the title having been held by Charles, Duke of Angoulême, natural son of Charles IX.—M.

- Tabourers are still to be found in some towns of Lower Languedoc and in most of those of Provence, where they perambulate the streets playing their instruments. They are in great request at all the country weddings and other festive gatherings, as their instruments supply the necessary accompaniment to the ancient Provençal dance, the farandole.—Ed.

- From the ritual for the Feast of the Holy Innocents.—M.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.