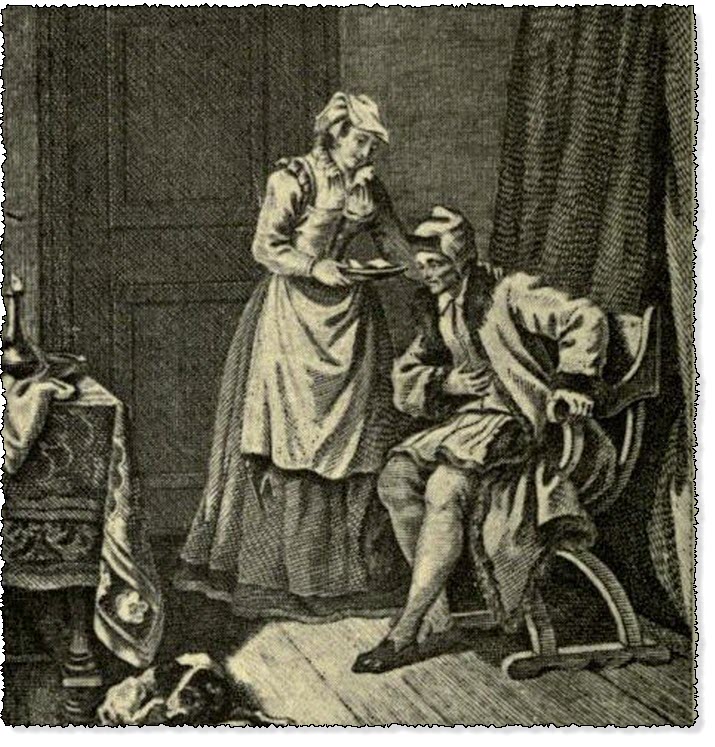

The apothecary's wife

The Heptameron - Day 7 - Tale 68 - The Apothecary's Wife Giving Poison To Her Husband

Summary of the Eighth Tale Told on the Seventh of the Heptameron

Tale 68 of the Heptameron

In the town of Pau in Beam there was an apothecary whom men called Master Stephen. He had married a virtuous wife and a thrifty, with beauty enough to content him. But just as he was wont to taste different drugs, so did he also with women, that he might be the better able to speak of all kinds. His wife was greatly tormented by this, and at last lost all patience; for he made no account of her except by way of penance during Holy Week.

One day when the apothecary was in his shop, and his wife had hidden herself behind him to listen to what he might say, a woman, who was "commère" to the apothecary, and was stricken with the same sickness as his own wife, came in, and, sighing, said to him—

"Alas, good godfather, I am the most unhappy woman alive. I love my husband better than myself, and do nothing but think of how I may serve and obey him; but all my labour is wasted, for he prefers the wickedest, foulest, vilest woman in the town to me. So, godfather, if you know of any drug that will change his humour, prithee give it me, and, if I be well treated by him, I promise to reward you by all means in my power."

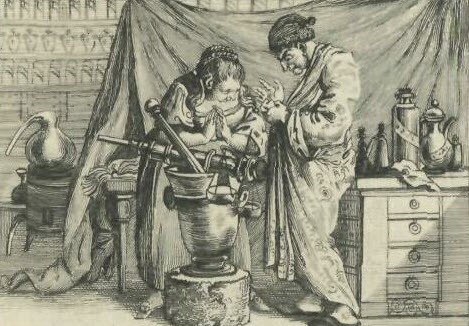

The apothecary, to comfort her, said that he knew of a powder which, if she gave it to her husband with his broth or roast, after the fashion of Duke's powder, (2) would induce him to entertain her in the best possible manner. The poor woman, wishing to behold this miracle, asked him what the powder was, and whether she could have some of it. He declared that there was nothing like powder of cantharides, of which he had a goodly store; and before they parted she made him prepare this powder, and took as much of it as was needful for her purpose. And afterwards she often thanked the apothecary, for her husband, who was strong and lusty, and did not take too much, was none the worse for it.

The apothecary's wife heard all this talk, and thought within herself that she had no less need of the recipe than her husband's "commère." Observing, therefore, the place where her husband put the remainder of the powder, she resolved that she would use some of it when she found an opportunity; and this she did within three or four days. Her husband, who felt a coldness of the stomach, begged her to make him some good soup, but she replied that a roast with Duke's powder would be better for him; whereupon he bade her go quickly and prepare it, and take cinnamon and sugar from the shop. This she did, not forgetting also to take the remainder of the powder given to the "commère," without any heed to dose, weight or measure.

The husband ate the roast, and thought it very good. Before long, however, he felt its effects, and sought to soothe them with his wife, but this he found was impossible, for he felt all on fire, in such wise that he knew not which way to turn. He then told his wife that she had poisoned him, and demanded to know what she had put into the roast. She forthwith confessed the truth, telling him that she herself required the recipe quite as much as his "commère." By reason of his evil plight, the poor apothecary could belabour her only with hard words; however, he drove her from his presence, and sent to beg the Queen of Navarre's apothecary (3) to come and see him. This the Queen's apothecary did, and whilst giving the other all the remedies proper for his cure (which in a short time was effected) he rebuked him very sharply for his folly in counselling another to use drugs that he was not willing to take himself, and declared that his wife had only done her duty, inasmuch as she had desired to be loved by her husband.

Thus the poor man was forced to endure the results of his folly in patience, and to own that he had been justly punished in being brought into such derision as he had proposed for another.

"Methinks, ladies, this woman's love was as indiscreet as it was great."

"Do you call it loving her husband," said Hircan, "to give him pain for the sake of the delight that she herself looked to have?"

"I believe," said Longarine, "she only desired to win back her husband's love, which she deemed to have gone far astray; and for the sake of such happiness there is nothing that a woman will not do." "Nevertheless," said Geburon, "a woman ought on no account to make her husband eat or drink anything unless, either through her own experience or that of learned folk, she be sure that it can do him no harm. Ignorance, however, must be excused, and hers was worthy of excuse; for the most blinding passion is love, and the most blinded of persons is a woman, since she has not strength enough to conduct so weighty a matter wisely."

Heptameron Story 68

"Geburon," said Oisille, "you are departing from your own excellent custom so as to make yourself of like mind with your fellows; but there are women who have endured love and jealousy in patience."

"Ay," said Hircan, "and pleasantly too; for the most sensible are those who take as much amusement in laughing at their husbands' doings, as their husbands take in secretly deceiving them. If you will make it my turn, so that the Lady Oisille may close the day, I will tell you a story about a wife and her husband who are known to all of us here."

"Begin, then," said Nomerfide; and Hircan, laughing, began thus:—

Footnotes:

- Mr W. Kelly has pointed out (Bohn's Heptameron, p. 395) that in France the godfather and godmother of a child are called in reference to each other compère and commère, terms implying mutual relations of an extremely friendly kind. "The same usage exists in all Catholic countries," adds Mr Kelly, "and one of the novels of the Decameron is founded on a very general opinion in Italy that an amorous connection between a compadre and his commadre partook almost of the nature of incest."

- Boaistuau and Gruget call this preparation poudre de Dun, as enigmatical an appellation as poudre de Duc. As for the specific supplied by the apothecary, the context shows that this was the same aphrodisiac as the Marquis de Sades put to such a detestable use at Marseilles in 1772, when, after fleeing from justice, he was formally sentenced to death, and broken, in effigy, upon the wheel. See P. Lacroix's Curiosités de l'histoire de France, IIème Série, Paris, 1858.—Ed.

- It was from her apothecary no doubt that Queen Margaret heard this story.—Ed.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.