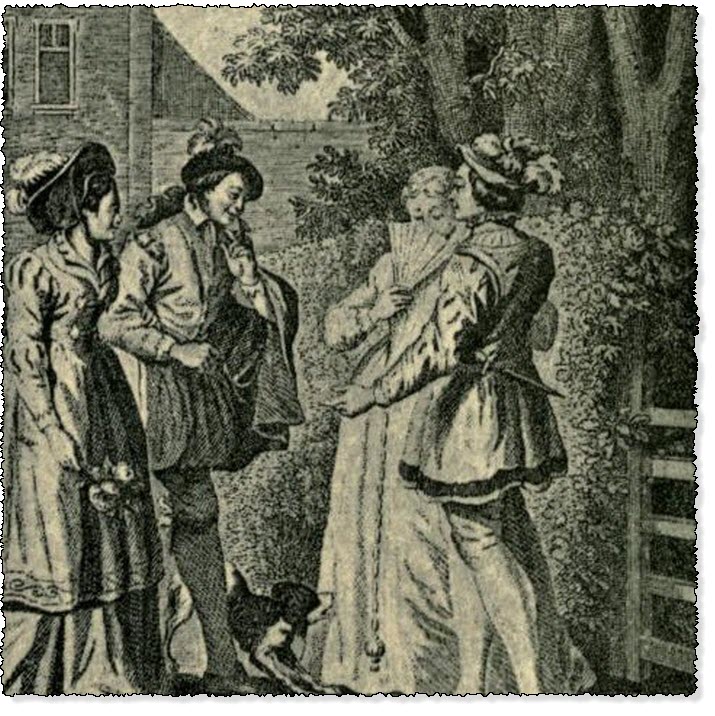

the Lovers Returning from Their Meeting in The Garden

The Heptameron - Day 5 - Tale 44 - the Lovers Returning from Their Meeting in The Garden

Summary of the Fourth Tale Told on the Fifth of the Heptameron

Tale 44 of the Heptameron

To the castle of Sedan once came a Grey Friar to ask my Lady of Sedan, who was of the house of Crouy, (2) for a pig, which she was wont to give to his Order every year as alms.

My Lord of Sedan, who was a prudent man and a merry talker, had the good father to eat at his table, and in order to put him on his mettle said to him, among other things—

"Good father, you do well to make your collection while you are yet unknown. I greatly fear that, if once your hypocrisy be found out, you will no longer receive the bread of poor children, earned by the sweat of their fathers."

The Grey Friar was not abashed by these words, but replied—

"Our Order, my lord, is so securely founded that it will endure as long as the world exists. Our foundation, indeed, cannot fail so long as there are men and women on the earth."

My Lord of Sedan, being desirous of knowing on what foundation the existence of the Grey Friars was thus based, urgently begged the father to tell him.

After making many excuses, the Friar at last replied—

"Since you are pleased to command me to tell you, you shall hear. Know, then, my lord, that our foundation is the folly of women, and that so long as there be a wanton or foolish woman in the world we shall not die of hunger."

My Lady of Sedan, who was very passionate, was in such wrath on hearing these words, that, had her husband not been present, she would have dealt harshly with the Grey Friar; and indeed she swore roundly that he should not have the pig that she had promised him; but the Lord of Sedan, finding that he had not concealed the truth, swore that he should have two, and caused them to be sent to his monastery.

"You see, ladies, how the Grey Friar, being sure that the favour of the ladies could not fail him, contrived, by concealing nothing of the truth, to win the favour and alms of men. Had he been a flatterer and dissembler, he would have been more pleasing to the ladies, but not so profitable to himself and his brethren."

The tale was not concluded without making the whole company laugh, and especially such among them as knew the Lord and Lady of Sedan. And Hircan said—"The Grey Friars, then, should never preach with intent to make women wise, since their folly is of so much service to the Order."

Heptameron Story 44

"They do not preach to them," said Parlamente, "with intent to make them wise, but only to make them think themselves so. Women who are altogether worldly and foolish do not give them much alms; nevertheless, those who think themselves the wisest because they go often to monasteries, and carry paternosters marked with a death's head, and wear caps lower than others, must also be accounted foolish, for they rest their salvation on their confidence in the holiness of wicked men, whom they are led by a trifling semblance to regard as demigods."

"But who could help believing them," said Ennasuite, "since they have been ordained by our prelates to preach the Gospel to us and rebuke our sins?"

"Those who have experienced their hypocrisy," said Parlamente, "and who know the difference between the doctrine of God and that of the devil."

"Jesus!" said Ennasuite. "Can you think that these men would dare to preach false doctrine?"

"Think?" replied Parlamente. "Nay, I am sure that they believe anything but the Gospel. I speak only of the bad among them; for I know many worthy men who preach the Scriptures in all purity and simplicity, and live without reproach, ambition, or covetousness, and in such chastity as is unfeigned and free. However, the streets are not paved with such as these, but are rather distinguished by their opposites; and the good tree is known by its fruit."

"In very sooth," said Ennasuite, "I thought we were bound on pain of mortal sin to believe all they tell us from the pulpit as truth, that is, when they speak of what is in the Holy Scriptures, or cite the expositions of holy doctrines divinely inspired."

"For my part," said Parlamente, "I cannot but see that there are men of very corrupt faith among them. I know that one of them, a Doctor of Theology and a Principal in their Order, (3) sought to persuade many of the brethren that the Gospel was no more worthy of belief than Cæsar's Commentaries or any other histories written by learned men of authority; and from the hour I heard that I would believe no preacher's word unless I found it in harmony with the Word of God, which is the true touchstone for distinguishing between truth and falsehood."

"Be assured," said Oisille, "that those who read it constantly and with humility will never be led into error by deceits or human inventions; for whosoever has a mind filled with truth cannot believe a lie."

"Yet it seems to me," said Simontault, "that a simple person is more readily deceived than another."

"Yes," said Longarine, "if you deem foolishness to be the same thing as simplicity."

"I affirm," replied Simontault, "that a good, gentle and simple woman is more readily deceived than one who is wily and wicked."

"I think," said Nomerfide, "that you must know of one overflowing with such goodness, and so I give you my vote that you may tell us of her."

"Since you have guessed so well," said Simontault, "I will indeed tell you of her, but you must promise not to weep. Those who declare, ladies, that your craftiness surpasses that of men would find it hard to bring forward such an instance as I am now about to relate, wherein I propose to show you not only the exceeding craftiness of a husband, but also the simplicity and goodness of his wife."

TALE XLIV. (B).

Concerning the subtlety of two lovers in the enjoyment of their love, and the happy issue of the latter. (4)In the city of Paris there lived two citizens of middling condition, of whom one had a profession, while the other was a silk mercer. These two were very old friends and constant companions, and so it happened that the son of the former, a young man, very presentable in good company, and called James, used often by his father's favour to visit the mercer's house. This, however, he did for the sake of the mercer's beautiful daughter named Frances, whom he loved; and so well did James contrive matters with her, that he came to know her to be no less loving than loved.

Whilst matters were in this state, however, a camp was formed in Provence in view of withstanding the descent of Charles of Austria, (5) and James, being called upon the list, was obliged to betake himself to the army. At the very beginning of the campaign his father passed from life into death, the tidings whereof brought him double sorrow, on the one part for the loss of his father, and on the other for the difficulty he should have on his return in seeing his sweetheart as often as he had hoped.

As time went on, the first of these griefs was forgotten and the other increased. Since death is a natural thing, and for the most part befalls the father before the children, the sadness it causes gradually disappears; but love, instead of bringing us death, brings us life through the procreation of children, in whom we have immortality, and this it is which chiefly causes our desires to increase.

James, therefore, when he had returned to Paris, thought or cared for nothing save how he might renew his frequent visits to the mercer's house, and so, under cloak of pure friendship for him, traffic in his dearest wares. On the other hand, during his absence, Frances had been urgently sought by others, both because of her beauty and of her wit, and also because she was long since come to marriageable years; but whether it was that her father was avaricious, or that, since she was his only daughter, he was over anxious to establish her well, he failed to perform his duty in the matter. This, however, tended but little to her honour, for in these days people speak ill of one long before they have any reason to do so, and particularly in aught that concerns the chastity of a beautiful woman or maid. Her father did not shut his ears or eyes to the general gossip, nor seek resemblance with many others who, instead of rebuking wrongdoing, seem rather to incite their wives and children to it, for he kept her with such strictness that even those who sought her with offers of marriage could see her but seldom, and then only in presence of her mother.

It were needless to ask whether James found all this hard of endurance. He could not conceive that such rigour should be without weighty reason, and therefore wavered greatly between love and jealousy. However, he resolved at all risks to learn the cause, but wished first of all to know whether her affection was the same as before; he therefore set about this, and coming one morning to church, he placed himself near her to hear mass, and soon perceived by her countenance that she was no less glad to see him than he was to see her. Accordingly, knowing that the mother was less stern than the father, he was sometimes, when he met them on their way to church, bold enough to accost them as though by chance, and with a familiar and ordinary greeting; all, however, being done expressly so that he might the better work his ends.

To be brief, when the year of mourning for his father was drawing to an end, he resolved, on laying aside his weeds, to cut a good figure and do credit to his forefathers; and of this he spoke to his mother, who approved his design; for having but two children, himself and a daughter already well and honourably mated, she greatly desired to see him suitably married. And, indeed, like the worthy lady that she was, she still further incited his heart in the direction of virtue by countless instances of other young men of his own age who were making their way unaided, or at least were showing themselves worthy of those from whom they sprang.

It now only remained to determine where they should equip themselves, and the mother said—

"I am of opinion, James, that we should go to our friend Master Peter,"—that is, to the father of Frances—"for, knowing us, he will not cheat us."

His mother was indeed tickling him where he itched; however, he held firm and replied—

"We will go where we may find the cheapest and the best. Still," he added, "for the sake of his friendship with my departed father, I am willing that we should visit him first."

Matters being thus contrived, the mother and son went one morning to see Master Peter, who made them welcome; for traders, as you know, are never backward in this respect. They caused great quantities of all kinds of silk to be displayed before them, and chose what they required; but they could not agree upon the price, for James haggled on purpose, because his sweetheart's mother did not come in. So at last they went away without buying anything, in order to see what could be done elsewhere. But James could find nothing so handsome as in his sweetheart's house, and thither after a while they returned.

The mercer's wife was now there and gave them the best reception imaginable, and after such bargaining as is common in shops of the kind, during which Peter's wife proved even harder than her husband, James said to her—

"In sooth, madam, you are very hard to deal with. I can see how it is; we have lost my father, and our friends recognise us no longer."

So saying, he pretended to weep and wipe his eyes at thought of his departed father; but 'twas done in order to further his design.

The good widow, his mother, took the matter in perfect faith, and on her part said—

"We are as little visited since his death as if we had never been known. Such is the regard in which poor widows are held!"

Upon this the two women exchanged fresh declarations of affection, and promised to see each other oftener than ever. While they were thus discoursing, there came in other traders, whom the master himself led into the back shop. Then the young man perceived his opportunity, and said to his mother—

"I have often on feast days seen this good lady going to visit the holy places in our neighbourhood, and especially the convents. Now if, when passing, she would sometimes condescend to take wine with us, she would do us at once pleasure and honour."

The mercer's wife, who suspected no harm, replied that for more than a fortnight past she had intended to go thither, that, if it were fair, she would probably do so on the following Sunday, and that she would then certainly visit the lady at her house. This affair being concluded, the bargain for the silk quickly followed, since, for the sake of a little money, 'twould have been foolish to let slip so excellent an opportunity.

When matters had been thus contrived, and the merchandise taken away, James, knowing that he could not alone achieve so difficult an enterprise, was constrained to make it known to a faithful friend named Oliver, and they took such good counsel together that nothing now remained but to put their plan into execution.

Accordingly, when Sunday was come, the mercer's wife and her daughter, on returning from worship, failed not to visit the widow, whom they found talking with a neighbour in a gallery that looked upon the garden, while her daughter was walking in the pathways with James and Oliver.

When James saw his sweetheart, he so controlled himself that his countenance showed no change, and in this sort went forward to receive the mother and her daughter. Then, as the old commonly seek the old, the three ladies sat down together on a bench with their backs to the garden, whither the lovers gradually made their way, and at last reached the place where were the other two. Thus meeting, they exchanged some courtesies and then began to walk about once more, whereupon the young man related his pitiful case to Frances, and this so well that, while unwilling to grant, she yet durst not refuse what he sought; and he could indeed see that she was in a sore strait. It must, however, be understood that, while thus discoursing, they often, to take away all ground for suspicion, passed and repassed in front of the shelter-place where the worthy dames were seated—talking the while on commonplace and ordinary matters, and at times disporting themselves through the garden.

At last, in the space of half-an-hour, when the good women had become well accustomed to this behaviour, James made a sign to Oliver, who played his part with the girl that was with him so cleverly, that she did not perceive the two lovers going into a close rilled with cherry trees, and well shut in by tall rose trees and gooseberry bushes. (6) They made show of going thither in order to gather some almonds which were in a corner of the close, but their purpose was to gather plums.

Accordingly, James, instead of giving his sweetheart a green gown, gave her a red one, and its colour even came into her face through finding herself surprised sooner than she had expected. And these plums of theirs being ripe, they plucked them with such expedition that Oliver himself had not believed it possible, but that he perceived the girl to droop her gaze and look ashamed. This taught him the truth, for she had before walked with head erect, with no fear lest the vein in her eye, which ought to be red, should take an azure hue. However, when James perceived her perturbation, he recalled her to herself by fitting remonstrances.

Nevertheless, while making the next two or three turns about the garden, she would not refrain from tears and sighs, or from saying again and again—"Alas! was it for this you loved me? If only I could have imagined it! Heavens! what shall I do? I am ruined for life. What will you now think of me? I feel sure you will respect me no longer, if, at least, you are one of those that love but for their own pleasure. Alas, why did I not die before falling into such an error?"

She shed many tears while uttering these words, but James comforted her with many promises and oaths, and so, before they had gone thrice again round the garden, or James had signalled to his comrade, they once more entered the close, but by another path. And there, in spite of all, she could not but receive more delight from the second green gown than from the first; from which moment her satisfaction was such that they took counsel together how they might see each other with more frequency and convenience until her father should see fit to consent.

In this matter they were greatly assisted by a young woman, who was neighbour to Master Peter; she had some kinship with James, and was a good friend to Frances. And in this way, from what I can understand, they continued without scandal until the celebration of the marriage, when Frances, being an only child, proved to be very rich for a trader's daughter. James had, however, to wait for the greater part of his fortune until the death of his father-in-law, for the latter was so grasping a man that he seemed to think one hand capable of robbing him of that which he held in the other. (7)

"In this story, ladies, you see a love affair well begun, well carried on, and better ended. For although it is a common thing among you men to scorn a girl or woman as soon as she has freely given what you chiefly seek in her, yet this young man was animated by sound and sincere love; and finding in his sweetheart what every husband desires in the girl he weds, and knowing, moreover, that she was of good birth, and discreet in all respects, save for the error into which he himself had led her, he would not act the adulterer or be the cause of an unhappy marriage elsewhere. And for this I hold him worthy of high praise."

"Yet," said Oisille, "they were both to blame, ay, and the third party also who assisted or at least concurred in a rape."

"Do you call that a rape," said Saffredent, "in which both parties are agreed? Is there any marriage better than one thus resulting from secret love? The proverb says that marriages are made in heaven, but this does not hold of forced marriages, nor of such as are made for money or are deemed to be completely sanctioned as soon as the parents have given their consent."

"You may say what you will," said Oisille, "but we must recognise that obedience is due to parents, or, in default of them, to other kinsfolk. Otherwise, if all were permitted to marry at will, how many horned marriages should we not find? Is it to be presumed that a young man and a girl of twelve or fifteen years can know what is good for them? If we examined into the happiness of marriages on the whole, we should find that at least as many love-matches have turned out ill as those that were made under compulsion. Young people, who do not know what is good for them, attach themselves heedlessly to the first that comes; then by degrees they find out their error and fall into others that are still greater. On the other hand, most of those who act under compulsion proceed by the advice of people who have seen more and have more judgment than the persons concerned, and so when these come to feel the good that was before unknown to them, they rejoice in it and embrace it with far more eagerness and affection."

"True, madam," said Hircan, "but you have forgotten that the girl was of full age and marriageable, and that she was aware of her father's injustice in letting her virginity grow musty rather than rub the rust off his crown pieces. And do you not know that nature is a jade? She loved and was loved; she found her happiness close to her hand, and she may have remembered the proverb, 'She that will not when she may, when she will she shall have nay.' All these things, added to her wooer's despatch, gave her no time to resist. Further, you have heard that immediately afterwards her face showed that some noteworthy change had been wrought in her. She was perhaps annoyed at the shortness of the time afforded her to decide whether the thing were good or bad, for no great pressing was needed to make her try a second time."

"Now, for my part," said Longarine, "I can find no excuse for such conduct, except that I approve the good faith shown by the youth who, comporting himself like an honest man, would not forsake her, but took her such as he had made her. In this respect, considering the corruption and depravity of the youth of the present day, I deem him worthy of high praise. I would not for all that seek to excuse his first fault, which, in fact, amounted to rape in respect to the daughter, and subornation with regard to the mother."

"No, no," said Dagoucin, "there was neither rape nor subornation. Everything was done by mere consent, both on the part of the mothers, who did not prevent it (though, indeed, they were deceived), and on that of the daughter, who was pleased by it, and so never complained."

"It was all the result," said Parlamente, "of the great kindliness and simplicity of the mercer's wife, who unwittingly led the maiden to the slaughter."

"Nay, to the wedding," said Simontault, "where such simplicity was no less profitable to the girl than it once was hurtful to one who suffered herself to be readily duped by her husband."

"Since you know such a story," said Nomerfide, "I give you my vote that you may tell it to us."

"I will indeed do so," said Simontault, "but you must promise not to weep. Those who declare, ladies, that your craftiness surpasses that of men, would find it hard to bring forward such an instance as I will now relate, wherein I propose to show you not only the great craftiness of a husband, but the exceeding simplicity and goodness of his wife."

Footnotes:

- This tale, though it figures in all the MSS., does not appear in Gruget's edition of the Heptameron, but is there replaced by the one that follows, XLIV. (B).—Ed.

- This Lady of Sedan is Catherine de Croï, daughter of Philip VI. de Croï, Count of Chimay. In 1491 she married Robert II. do la Marck, Duke of Bouillon, Lord of Sedan, Fleuranges, &c., who was long the companion in arms of Bayard and La Trémoïlle. Robert II. lost the duchy of Bouillon through the conquests of Charles V., and one of the clauses of the treaty of Cambrai (the "Ladies' Peace") was that Francis I. would in no wise assist him to regain it. His eldest son by Catherine de Croï was the celebrated Marshal de Fleuranges, "the young adventurer," who left such curious memoirs behind him. Robert II. died in 1535, his son surviving him a couple of years.—Anselme's Histoire Généalogique, vol. vii. p. 167.—L. and B. J.

- In MS. No. 1520 this passage runs, "a Doctor of Theology named Colimant, a great preacher and a Principal in their Order." However, none of the numerous works on the history of the Franciscans makes any mention of a divine called Colimant.—B. J.

- This is the tale given by Gruget in his edition of the Heptameron, in lieu of the preceding one.—Ed.

- Charles V. entered Provence by way of Piedmont in the summer of 1536, and invested Marseilles. A scarcity of supplies and much sickness among his troops compelled him, however, to raise the siege.—M.

- Large gardens and enclosures were then plentiful in the heart of Paris. Forty years ago, when the Boulevard Sebastopol was laid out, it was found that many of the houses in the ancient Rues St. Martin and St. Denis had, in their rear, gardens of considerable extent containing century-old trees, the existence of which had never been suspected by the passers-by in those then cramped and dingy thoroughfares.—M.

- This reminds one of Moliere's Harpagon, when he requires La Flèche to show him his hands. See L'Avare, act i. sc. iii.—M.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.