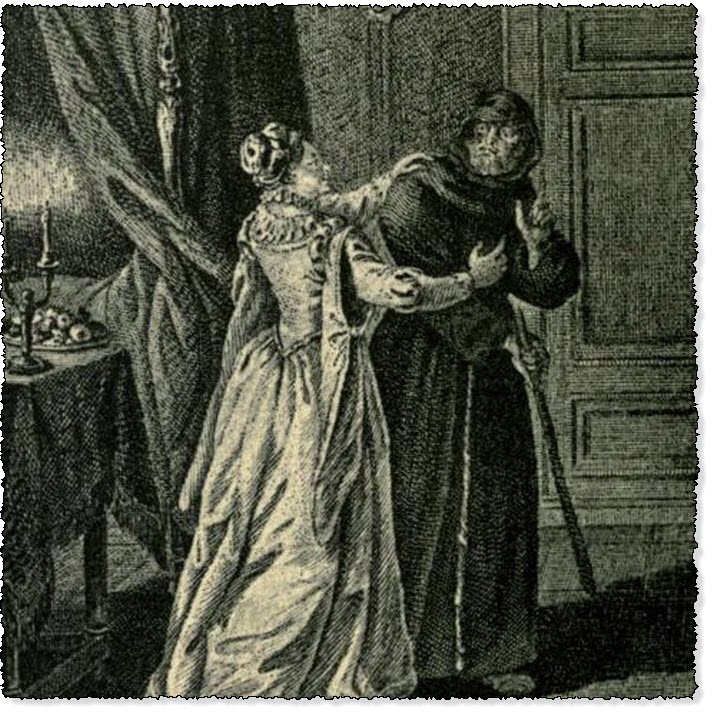

The Lady Embracing The Supposed Friar

The Heptameron - Day 5, Tale 35 - the Lady Embracing The Supposed Friar

TALE XXXV.

The affection of a lady of Pampeluna—who, thinking that there was no danger in spiritual love, had striven to insinuate herself into the good graces of a Grey Friar—was subdued by her husband's prudence in such wise that, without telling her that he knew aught of the matter, he brought her mortally to hate that which she had most dearly loved, and wholly to devote herself to him.

In the town of Pampeluna there lived a lady who was accounted beautiful and virtuous, as well as the chastest and most pious in the land. She loved her husband, and was so obedient to him that he had entire trust in her. This lady was constantly present at Divine service and at sermons, and she used to persuade her husband and children to be hearers with her. She had reached the age of thirty years, at which women are wont to claim discretion rather than beauty, when on the first day of Lent she went to the church to receive the emblem of death. (1) Here she found that the sermon was beginning, the preacher being a Grey Friar, a man esteemed holy by all the people on account of his great austerity and goodness of life, which made him thin and pale, yet not to such a point as to prevent him from being one of the handsomest men imaginable.

The lady listened piously to his sermon, her eyes being fixed on this reverend person, and her ears and mind ready to hearken to what he said. And so it happened that the sweetness of his words passed through the lady's ears even to her heart, while the comeliness and grace of his countenance passed through her eyes and so smote her soul that she was as one entranced. When the sermon was over, she looked carefully to see where the Friar would celebrate mass, (2) and there she presented herself to take the ashes from his hand. The latter was as fair and white as any lady's, and this pious lady paid more attention to it than to the ashes which it gave her.

1 To receive the ashes on Ash Wednesday.—M. 2 That is, in which of the chapels. A friar would not officiate at the high altar.—Ed.

Feeling persuaded that a spiritual love such as this, with any pleasure that she might derive from it, could not wound her conscience, she failed not to go and hear the sermon every day and to take her husband with her; and they both gave such great praise to the preacher, that they spoke of nought beside at table or elsewhere. At last this supposed spiritual fire became so carnal that the poor lady's heart in which it glowed began to consume her whole body; and just as she had been slow to feel the flame, so did she now swiftly kindle, and feel all the delights of passion, before she knew that she even was in love. Being thus surprised by her enemy, Love, she offered no further resistance to his commands. But the worst was that the physician who might have cured her ills was ignorant of her distemper; for which reason, banishing the dread she should have had of making known her foolishness to a man of wisdom, and her vice and wickedness to a man of virtue and honour, she proceeded to write to him of the love she bore him, doing this, to begin with, as modestly as she could. And she gave her letter to a little page, telling him what he had to do, and saying that he was to be careful above all things that her husband should not see him going to the monastery of the Grey Friars.

The page, desiring to take the shortest way, passed through a street in which his master was sitting in a shop. Seeing him pass, the gentleman came out to observe whither he was going, and when the page perceived him, he was quite confused, and hid himself in a house. Noticing this, his master followed him, took him by the arm and asked him whither he was bound. Finding also that he had a terrified look and made but empty excuses, he threatened to beat him soundly if he did not confess the truth.

"Alas, sir," said the poor page, "if I tell you, my lady will kill me."

Heptameron Story 35

The gentleman, suspecting that his wife was making some bargain without his knowledge, promised the page that he should come by no hurt, and should be well rewarded, if he told the truth; whereas, if he lied, he should be thrown into prison for life. Thereupon the little page, eager to have the good and to avoid the evil, told him the whole story, and showed him the letter that his mistress had written to the preacher. At this her husband was the more astonished and grieved, as he had all his life long been persuaded of the faithfulness of his wife, in whom he had never discovered a fault.

Nevertheless, being a prudent man, he concealed his anger, and so that he might fully learn his wife's intention, he sent a reply as though from the preacher, thanking her for her goodwill, and declaring that his was as great towards her. The page, having sworn to his master that he would conduct the matter with discretion, (3) brought the counterfeit letter to his mistress, who was so greatly rejoiced by it that her husband could see that her countenance was changed; for, instead of growing lean from the fasts of Lent, she now appeared fairer and fresher than before they began.

3 This is borrowed from MS. 1520. In our MS. the passage runs, "The page having shown his master how to conduct this affair," &c.—L.

It was now mid-Lent, but no thought of the Passion or Holy Week prevented the lady from writing her frenzied fancies to the preacher according to her wont; and when he turned his eyes in her direction, or spoke of the love of God, she thought that all was done or said for love of her; and so far as her eyes could utter her thoughts, she did not spare them.

The husband never failed to return her similar answers, but after Easter he wrote to her in the preacher's name, begging her to let him know how he could secretly see her. She, all impatient for the meeting, advised her husband to go and visit some estates of theirs in the country, and this he agreed to do, hiding himself, however, in the house of a friend. Then the lady failed not to write to the preacher that it was time he should come and see her, since her husband was in the country.

The gentleman, wishing thoroughly to try his wife's heart, then went to the preacher, and begged him for the love of God to lend him his robe. The preacher, who was a man of worth, replied that the rules of his Order forbade it, and that he would never lend his robe for a masquerade. (4) The gentleman assured him, however, that he would make no evil use of it, and that he wanted it for a matter necessary to his happiness and his salvation. Thereupon the Friar, who knew the other to be a worthy and pious man, lent it to him; and with this robe, which covered his face so that his eyes could not be seen, the gentleman put on a false beard and a false nose, each similar to the preacher's. He also made himself of the same height by means of cork. (5)

4 This may be compared with the episode of Tappe-coue or Tickletoby in Pantagruel:—"Villon, to dress an old clownish father grey-beard, who was to represent God the Father [at the performance of a mystery], begged of Friar Stephen Tickletoby, sacristan to the Franciscan Friars of the place, to lend him a cope and a stole. Tickletoby refused him, alleging that by their provincial statutes it was rigorously forbidden to give or lend anything to players. Villon replied that the statute reached no further than farces, drolls, antics, loose and dissolute games.... Tickletoby, however, peremptorily bid him provide himself elsewhere, if he would, and not to hope for anything out of his monastical wardrobe.... Villon gave an account of this to the players as of a most abominable action; adding that God would shortly revenge himself and make an example of Tickletoby."— Urquhart's Works of Rabelais, Pantagruel, (Book IV. xiii.)—M. 5 In Boaistuau's edition the sentence runs, "and by putting some cork in his shoes made himself of the same height as the preacher."—L.

Thus garmented, he repaired in the evening to his wife's apartment, where she was very piously awaiting him. The poor fool did not tarry for him to come to her, but ran to embrace him like a woman bereft of reason. Keeping his face bent down lest he should be recognised, he then began making the sign of the cross, and pretended to flee from her, saying the while nothing but—

"Temptation! temptation!"

"Alas, father," said the lady, "you are indeed right, for there is no stronger temptation than that which proceeds from love. But for this you have promised me a remedy; and I pray you, now that we have time and opportunity, to take pity upon me."

So saying, she strove to embrace him, but he ran all round the room, making great signs of the cross, and still crying—

"Temptation! temptation!"

However, when he found that she was urging him too closely, he took a big stick that he had beneath his cloak and beat her so sorely as to end her temptation, and that without being recognised by her. Then he immediately went and returned the robe to the preacher, assuring him that it had brought him good fortune.

On the morrow, pretending to come from a distance, he returned home and found his wife in bed, when, as though he knew nothing of her sickness, he asked her the cause of it; and she replied that it was a catarrh, and that she could move neither hand nor foot. The husband, who was much inclined to laugh, made as though he were greatly grieved, and as if to cheer her told her that he had bidden the saintly preacher to supper that evening. But she quickly replied—

"God forbid, sweetheart, that you should ever invite such folk. They bring misfortune into every house they visit."

"Why, sweet," said the husband, "how is this? You have always greatly praised this man, and for my own part I believe that if there be a holy man on earth, it is he."

"They are good in church and when preaching," answered the lady, "but in our houses they are very antichrists. I pray you, sweet, let me not see him, for with my present sickness it would be enough to kill me."

"Since you do not wish to see him," returned the husband, "you shall not do so, but I must have him here to supper."

"Do what you will," she replied, "but let me not see him, for I hate such folk as I do the devil."

After giving supper to the good father, the husband said to him—

"Father, I believe you to be so beloved of God, that He will refuse you no request. I therefore entreat you to take pity on my poor wife, who for a week past has been possessed by the evil spirit in such a way, that she tries to bite and scratch every one. She cares for neither cross nor holy water, but I verily believe that if you will lay your hand upon her the devil will come forth, and I therefore earnestly entreat you to do so."

"My son," said the good father, "all things are possible to a believer. Do you, then, firmly believe that God in His goodness never refuses those that in faith seek grace from Him?"

"I do, father," said the gentleman.

"Be also assured, my son," said the friar, "that He can do what He will, and that He is even as powerful as He is good. Let us go, then, strong in faith to withstand this roaring lion, and to pluck from him his prey, whom God has purchased by the blood of Jesus Christ, His Son."

Accordingly, the gentleman led this worthy man to where his wife lay on a little bed. She, thinking that it was the Friar who had beaten her, was much astonished to see him there and exceedingly wrathful; however, her husband being present, she cast down her eyes, and remained dumb.

"As long as I am with her," said the husband to the holy man, "the devil scarcely torments her. But sprinkle some holy water upon her as soon as I am gone, and you will soon see how the evil spirit does his work."

The husband left them alone together, and waited at the door to see how they would behave. When the lady saw no one with her but the good father, she began to cry out like a woman bereft of reason, calling him rascal, villain, murderer, betrayer. At this, the good father, thinking that she was surely possessed by an evil spirit, tried to put his hands upon her head, in order to utter his prayers upon it; but she scratched and bit him in such a fashion, that he was obliged to speak at a greater distance, whence, throwing a great deal of holy water upon her, he pronounced many excellent prayers.

When the husband saw that the Friar had done his duty, he came into the room and thanked him for his trouble. At his entrance his wife ceased her cursings and revilings, and meekly kissed the cross in the fear she had of him. But the holy man, having seen her in so great a frenzy, firmly believed that Our Lord had cast out the devil in answer to his prayer, and he went away, praising God for this wonderful miracle.

The husband, seeing that his wife was well punished for her foolish fancy, did not tell her of what he had done. He was content to have subdued her affection by his own prudence, and to have so dealt with her that she now hated mortally what she had formerly loved, and, loathing her folly, devoted herself to her husband and household more completely than she had ever done before.

"In this story, ladies, you see the good sense of a husband and the frailty of a woman of repute. I think that if you look carefully into this mirror you will no longer trust to your own strength, but will learn to have recourse to Him who holds your honour in His hand."

"I am well pleased," said Parlamente, "to find you become a preacher to the ladies, and I should be even more so if you would make these fine sermons to all those with whom you speak."

"Whenever you are willing to listen to me," said Hircan, "I promise you that I will say as much."

"In other words," said Simontault, "when you are not present, he will speak in a different fashion."

"He will do as he pleases," said Parlamente, "but for my content I wish to believe that he always speaks in this way. At all events, the example he has brought forward will be profitable to those who believe that spiritual love is not dangerous. In my opinion it is more so than any other."

"Yet," said Oisille, "it seems to me that to love a worthy, virtuous and God-fearing man is in nowise a matter for scorn, and that one cannot but be the better for it."

"Madam," said Parlamente, "I pray you believe that no one can be more simple or more easily deceived than a woman who has never loved. For in itself love is a passion that seizes upon the heart before one is aware of it, and so pleasing a passion is it that, if it can make use of virtue as a cloak, it will scarcely be recognised before some mischief has come of it."

"What mischief," asked Oisille, "can come of loving a worthy man?"

"Madam," said Parlamente, "there are a good many men that are esteemed worthy, but to be worthy in respect of the ladies, and to be careful for their honour and conscience—not one such man as that could, I think, be found in these days. Those who think otherwise, and put their trust in men, find at last that they have been deceived, and, having begun such intimacy with obedience to God, will often end it with obedience to the devil. I have known many who, under pretext of speaking about God, began an intimacy from which they could not withdraw when at last they wished to do so, being held in subjection by this semblance of virtue. A vicious love perishes of its own nature, and cannot continue in a good heart, but virtuous love has bonds of silk so fine that one is caught in them before they are seen."

"According to you," said Ennasuite, "no woman should ever love a man; but your law is too harsh a one to last."

"I know that," said Parlamente, "but none the less must I desire that every one were as content with her own husband as I am with mine."

Ennasuite, who felt that these words touched her, changed colour and said—

"You ought to believe every one the same at heart as yourself, unless, indeed, you think yourself more perfect than all others."

"Well," said Parlamente, "to avoid dispute, let us see to whom Hircan will give his vote."

"I give it," Hircan replied, "to Ennasuite, in order to make amends to her for what my wife has said."

"Then, since it is my turn," said Ennasuite, "I will spare neither man nor woman, that all may fare alike. I see right well that you are unable to subdue your hearts to acknowledge the virtue and goodness of men, for which reason I am obliged to resume the discourse with a story like to the last."

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.