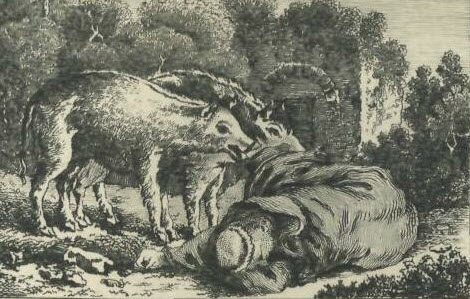

the Grey Friar Imploring The Butcher to Spare his Life

The Heptameron - the Grey Friar Imploring The Butcher to Spare his Life

TALE XXXIV.

Two Grey Friars, while listening to secrets that did not concern them, misunderstood the language of a butcher and endangered their lives. (1)

Between Nyort and Fors there is a village called Grip, (2) which belongs to the Lord of Fors.

1 This story is evidently founded upon fact; the incidents must have occurred prior to 1530.—L. 2 Gript, a little village on the Courance, eight miles south of Niort (Deux-Sèvres), produces some of the best white wine in this part of France. Its church of St. Aubin stood partly in the diocese of Poitiers, partly in that of Saintes, the altar being in the former, and the door in the latter one. This is the only known instance of the kind in France. Fors, a few miles distant from Gript, was a fief which Catherine, daughter of Artus de Vivonne, brought in marriage to James Poussart, knight, who witnessed the Queen of Navarre's marriage contract, signing himself, "Seigneur de Fors, Bailly du Berry." He is often mentioned in the Queen's letters.—See Génin's Lettres de Marguerite, &c, pp. 243-244, 258-259, 332.—L. and M.

It happened one day that two Grey Friars, on their way from Nyort, arrived very late at this place, Grip, and lodged in the house of a butcher. Now, as there was nothing between their host's room and their own but a badly joined partition of wood, they had a mind to listen to what the husband might say to his wife when he was in bed with her, and accordingly they set their ears close to the head of their host's bed. He, having no thought of his lodgers, spoke privately with his wife concerning their household, and said to her—

"I must rise betimes in the morning, sweetheart, and see after our Grey Friars. One of them is very fat, and must be killed; we will salt him forthwith and make a good profit off him."

And although by "Grey Friars" he meant his pigs, the two poor brethren, on hearing this plot, felt sure that they themselves were spoken of, (3) and so waited with great fear and trembling for the dawn.

3 The butcher doubtless called his pigs "Grey Friars" in allusion to the latter's gluttony and uncleanly habits. Pigs are even nowadays termed moines (monks) by the peasantry in some parts of France. Moreover, the French often render our expression "fat as a pig" by "fat as a monk."—Ed.

One of them was very fat and the other rather lean. The fat one wished to confess himself to his companion, saying that a butcher who had lost the love and fear of God would think no more of slaughtering him than if he were an ox or any other beast; and adding that as they were shut up in their room and could not leave it without passing through that of their host, they must needs look upon themselves as dead men, and commend their souls to God. But the younger Friar, who was not so overcome with fear as his comrade, made answer that, as the door was closed against them, they must e'en try to get through the window, for, whatever befel them, they could meet with nothing worse than death; to which the fat Friar agreed.

The young one then opened the window, and, finding that it was not very high above the ground, leaped lightly down and fled as fast and as far as he could, without waiting for his companion. The latter attempted the same hazardous jump, but in place of leaping, fell so heavily by reason of his weight, that one of his legs was sorely hurt, and he could not rise from the ground.

Heptameron Story 34

Finding himself forsaken by his companion and being unable to follow him, he looked around him to see where he might hide, and could espy nothing save a pigsty, to which he dragged himself as well as he could. And as he opened the door to hide himself within, out rushed two huge pigs, whose place the unhappy Friar took, closing the little door upon himself, and hoping that, when he heard the sound of passers-by, he would be able to call out and obtain assistance.

As soon as the morning was come, however, the butcher got ready his big knives, and bade his wife bear him company whilst he went to slaughter his fat pig. And when he reached the sty in which the Grey Friar lay concealed, he opened the little door and began to call at the top of his voice—

"Come out, Master Grey Friar, come out! I intend to have some of your chitterlings to-day."

The poor Friar, who was not able to stand upon his leg, crawled on all-fours out of the sty, crying for mercy as loud as he could. But if the hapless Friar was in great terror, the butcher and his wife were in no less; for they thought that St. Francis was wrathful with them for calling a beast a Grey Friar, and therefore threw themselves upon their knees asking pardon of St. Francis and his Order. Thus, the Friar was crying to the butcher for mercy on the one hand, and the butcher to the Friar on the other, in such sort that a quarter of an hour went by before they felt safe from each other.

Perceiving at last that the butcher intended him no hurt, the good father told him the reason why he had hidden himself in the sty. Then was their fear turned to laughter, except, indeed, that the poor Friar's leg was too painful to suffer him to be merry. However, the butcher brought him into the house, where he caused the hurt to be carefully dressed.

His comrade, who had deserted him in his need, ran all night long, and in the morning came to the house of the Lord of Fors, where he lodged a complaint against the butcher, whom he suspected of killing his companion, seeing that the latter had not followed him. The Lord of Fors forthwith sent to Grip to learn the truth, and this, when known, was by no means the cause of tears. And he failed not to tell the story to his mistress the Duchess of Angoulême, mother of King Francis, first of that name. (4)

4 Many modern stories and anecdotes have been based on this amusing tale.—Ed.

"You see, ladies, how bad a thing it is to listen to secrets that do not concern us, and to misunderstand what other people say."

"Did I not know," said Simontault, "that Nomer-fide would give us no cause to weep, but rather to laugh? And I think that we have all done so very heartily."

"How comes it," said Oisille, "that we are more ready to be amused by a piece of folly than by something wisely done?"

"Because," said Hircan, "the folly is more agreeable to us, for it is more akin to our own nature, which of itself is never wise. And like is fond of like, the fool of folly, and the wise man of discretion. But I am sure," he continued, "that no one, whether foolish or wise, could help laughing at this story."

"There are some," said Geburon, "whose hearts are so bestowed on the love of wisdom that, whatever they may hear, they cannot be made to laugh. They have a gladness of heart and a moderate content such as nought can move."

"Who are they?" asked Hircan.

"The philosophers of olden days," said Geburon. "They were scarcely sensible of either sadness or joy, or at least they gave no token of either, so great a virtue did they deem the conquest of themselves and their passions. I too think, as they did, that it is well to subdue a wicked passion, but a victory over a natural passion, and one that tends to no evil, appears useless in my eyes."

"And yet," added Geburon, "the ancients held it for a great virtue."

"It is not maintained," said Saffredent, "that they all were wise. They had more of the appearance of sense and virtue than of the reality."

"Nevertheless, you will find that they rebuke everything bad," said Geburon. "Diogenes himself, even, trod on the bed of Plato, who was too fond (5) of rare and precious things for his taste, and this in order to show that he despised Plato's vanity and greed, and would put them under foot. 'I trample with contempt,' said he, 'upon the pride of Plato.'"

"But you have not told all," said Saffredent, "for Plato retorted that he did so from pride of another kind."

"In truth," said Parlamente, "it is impossible to accomplish the conquest of ourselves without extraordinary pride. And this is the vice that we should fear most of all, for it springs from the death and destruction of all the virtues."

"Did I not read to you this morning," said Oisille, "that those who thought themselves wiser than other men, since by the sole light of reason they had come to recognise a God, creator of all things, were made more ignorant and irrational not only than other men, but than the very brutes, and this because they did not ascribe the glory to Him to whom it was due, but thought that they had gained the knowledge they possessed by their own endeavours? For having erred in their minds by ascribing to themselves that which pertains to God alone, they manifested their errors by disorder of body, forgetting and perverting their natural sex, as St. Paul to-day doth tell us in the Epistle that he wrote to the Romans." (6)

5 The French word here is curieux, which in Margaret's time implied one fond of rare and precious things.—B. J 6 Romans i. 26, 27.—Ed.

"There is none among us," said Parlamente, "but will confess, on reading that Epistle, that outward sin is but the fruit of infelicity dwelling within, which, the more it is hidden by virtue and marvels, is the more difficult to pluck out."

"We men," said Hircan, "are nearer to salvation than you are, for we do not conceal our fruits, and so the root is readily known; whereas you, who dare not display the fruit, and who do so many seemingly fair deeds, are hardly aware of the root of pride that is growing beneath so brave a surface."

"I acknowledge," said Longarine, "that if the Word of God does not show us by faith the leprosy of unbelief that lurks in the heart, yet God is very merciful to us when He allows us to fall into some visible wrongdoing whereby the hidden plague may be made manifest. Happy are they whom faith has so humbled that they have no need to test their sinful nature by outward acts."

"But just look where we are now," said Simontault. "We started from a foolish tale, and we are now fallen into philosophy and theology. Let us leave these disputes to such as are more fitted for such speculation, and ask Nomerfide to whom she will give her vote."

"I give it," she said, "to Hircan, but I commend to him the honour of the ladies."

"You could not have commended it in a better place," said Hircan, "for the story that I have ready is just such a one as will please you. It will, nevertheless, teach you to acknowledge that the nature of men and women is of itself prone to vice if it be not preserved by Him to whom the honour of every victory is due. And to abate the pride that you display when a story is told to your honour, I will tell you one of a different kind that is strictly true."

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.