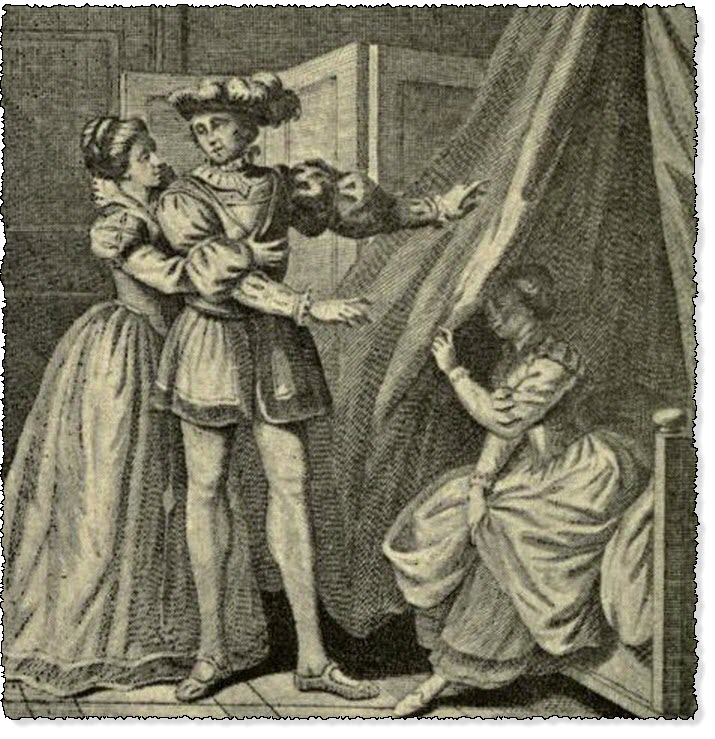

The Lady Discovering Her Husband With The Waiting-woman

The Heptameron - Day 6 - Tale 59 - The Lady Discovering Her Husband With The Waiting-woman

Summary of the Ninth Tale Told on the Sixth of the Heptameron

Tale 59 of the Heptameron

The lady of your story was wedded to a rich gentleman of high and ancient lineage, and had married him on account of the great affection that they bore to one another.

Being a woman most pleasant of speech, she by no means concealed from her husband that she had lovers whom she made game of for her pastime, and, at first, her husband shared in her pleasure. But at last this manner of life became irksome to him, for on the one part he took it ill that she should hold so much converse with those that were no kinsfolk or friends of his own, and on the other, he was greatly vexed by the expense to which he was put in sustaining her magnificence and in following the Court.

He therefore withdrew to his own house as often as he was able, but so much company came thither to see him that the expenses of his household became scarcely any less, for, wherever his wife might be, she always found means to pass her time in sports, dances, and all such matters as youthful dames may use with honour. And when sometimes her husband told her, laughing, that their expenses were too great, she would reply that she promised never to make him a "coqu" or cuckold, but only a "coquin," that is, a beggar; for she was so exceedingly fond of dress, that she must needs have the bravest and richest at the Court. (1) Her husband took her thither as seldom as possible, but she did all in her power to go, and to this end behaved in a most loving fashion towards her husband, who would not willingly have refused her a much harder request.

Now one day, when she had found that all her devices could not induce him to make this journey to the Court, she perceived that he was very pleasant in manner with a chamber-woman (2) she had, and thereupon thought she might turn the matter to her own advantage. Taking the girl apart, she questioned her cleverly, using both wiles and threats, in such wise that the girl confessed that, ever since she had been in the house, not a day had passed on which her master had not sought her love; but (she added) she would rather die than do aught against God and her honour, more especially after the honour which the lady had done her in taking her into her service, for this would make such wickedness twice as great.

On hearing of her husband's unfaithfulness, the lady immediately felt both grief and joy. Her grief was that her husband, despite all his show of loving her, should be secretly striving to put her to so much shame in her own household, and this when she believed herself far more beautiful and graceful than the woman whom he sought in her stead. But she rejoiced to think that she might surprise her husband in such manifest error that he would no longer be able to reproach her with her lovers, nor with her desire to dwell at Court; and, to bring this about, she begged the girl gradually to grant her husband what he sought upon certain conditions that she made known to her.

The girl was minded to make some difficulty, but when her mistress warranted the safety both of her life and of her honour, she consented to do whatever might be her pleasure.

The gentleman, on continuing his pursuit of the girl, found her countenance quite changed towards him, and therefore urged his suit more eagerly than had been his wont; but she, knowing by heart the part she had to play, made objection of her poverty, and said that, if she complied with his desire, she would be turned away by her mistress, in whose service she looked to gain a good husband.

The gentleman forthwith replied that she need give no thought to any such matters, since he would bestow her in marriage more profitably than her mistress would be able to do, and further, would contrive the matter so secretly that none would know of it.

Upon this they came to an agreement, and, on considering what place would be most suited for such a fine business, the girl said that she knew of none better or more remote from suspicion than a cottage in the park, where there was a chamber and a bed suitable for the occasion.

The gentleman, who would not have thought any place unsuitable, was content with the one she named, and was very impatient for the appointed day and hour to come.

The girl kept her word to her mistress, and told her in full the whole story of the plan, and how it was to be put into execution on the morrow after dinner. She would not fail, said she, to give a sign when the time came to go to the cottage, and she begged her mistress to be watchful, and in no wise fail to be present at the appointed hour, in order to save her from the danger into which her obedience was leading her.

This her mistress swore, begging her to be without fear, and promising that she would never forsake her, but would protect her from her husband's wrath.

When the morrow was come and dinner was over, the gentleman was more pleasant with his wife than ever, and although this was not very agreeable to her, she dissembled so well that he did not perceive the truth.

After dinner she asked him how he was minded to pass away the time, and he answered that he knew of nothing better than to play at "cent." (3) Forthwith everything was made ready for the game, but the lady pretended that she did not care to take part in it, and would find diversion enough in looking at the players.

Just before he sat down to play, the gentleman failed not to ask the girl to remember her promise to him, and while he was playing she passed through the room, making a sign to her mistress which signified that she was about to set out on the pilgrimage she had to make. The sign was clearly seen by the lady, but her husband perceived nothing of it.

An hour later, however, one of his servants made him a sign from a distance, whereupon he told his wife that his head ached somewhat, and that he must needs rest and take the air. She, knowing the nature of his sickness as well as he did himself, asked him whether she should play in his stead, and he consented, saying that he would very soon return. However, she assured him that she could take his place for a couple of hours without weariness.

So the gentleman withdrew to his room, and thence by an alley into his park.

The lady, who knew another and shorter way, waited for a little while, and then, suddenly feigning to be seized with colic, gave her hand at play to another.

As soon as she was out of the room, she put off her high-heeled shoes and ran as quickly as she could to the place, where she had no desire that the bargain should be struck without her. And so speedily did she arrive, that, when she entered the room by another door, her husband was but just come in. Then, hiding herself behind the door, she listened to the fair and honest discourse that he held to her maid. But when she saw that he was coming near to the criminal point, she seized him from behind, saying—

"Nay, I am too near that you should take another."

It is needless to ask whether the gentleman was in extreme wrath, both at being balked of the delight he had looked to obtain, and at having his wife, whose affection he now greatly feared to lose for ever, know more of him than he desired. He thought, however, that the plot had been contrived by the girl, and (without speaking to his wife) he ran after her with such fury that, had not his wife rescued her from his hands, he would have killed her. He declared that she was the wickedest jade he had ever known, and that, if his wife had waited to see the end, she would have found that he was only mocking her, for, instead of doing what she expected, he would have chastised her with rods.

But his wife, knowing what words of the sort were worth, set no value upon them, and addressed such reproaches to him that he was in great fear lest she should leave him. He promised her all that she asked, and, after her sage reproaches, confessed that it was wrong of him to complain that she had lovers; since a fair and honourable woman is none the less virtuous for being loved, provided that she do or say nothing contrary to her honour; whereas a man deserves heavy punishment when he is at pains to pursue a woman that loves him not, to the wronging of his wife and his own conscience. He would therefore, said he, never more prevent his wife from going to Court, nor take it ill that she should have lovers, for he knew that she spoke with them more in jest than in affection.

Heptameron Story 59

This talk was not displeasing to the lady, for it seemed to her that she had gained an important point. Nevertheless she spoke quite to the contrary, pretending that she had no delight in going to Court, since she no longer possessed his love, without which all assemblies were displeasing to her; and saying that a woman who was truly loved by her husband, and who loved him in return, as she did, carried with her a safe-conduct that permitted her to speak with one and all, and to be derided by none.

The poor gentleman was at so much pains to assure her of the love he bore her, that at last they left the place good friends. That they might not again fall into such trouble, he begged her to turn away the girl through whom he had undergone so much distress. This she did, but did it by bestowing her well and honourably in marriage, and at her husband's expense.

And, to make the lady altogether forget his folly, the gentleman soon took her to Court, in such style and so magnificently arrayed that she had good reason to be content.

"This, ladies, was what made me say I did not find the trick she played upon one of her lovers a strange one, knowing, as I did, the trick she had played upon her husband."

"You have described to us a very cunning wife and a very stupid husband," said Hircan. "Having advanced so far, he ought not to have come to a standstill and stopped on so fair a road."

"And what should he have done?" said Longarine.

"What he had taken in hand to do," said Hircan, "for his wife was no less wrathful with him for his intention to do evil than she would have been had he carried the evil into execution. Perchance, indeed, she would have respected him more if she had seen that he was a bolder gallant."

"That is all very well," said Ennasuite, "but where will you find a man to face two women at once? His wife would have defended her rights and the girl her virginity."

"True," said Hircan, "but a strong bold man does not fear to assail two that are weak, nor will he ever fail to vanquish them."

"I readily understand," said Ennasuite, "that if he had drawn his sword he might have killed them both, but otherwise I cannot see that he had any means of escape. I pray you, therefore, tell us what you would have done?"

"I should have taken my wife in my arms," said Hircan, "and have carried her out. Then I should have had my own way with her maid by love or by force."

"'Tis enough, Hircan," said Parlamente, "that you know how to do evil."

"I am sure, Parlamente," he replied, "that I do not scandalise the innocence in whose presence I speak, and by what I have said I do not mean that I support a wicked deed. But I wonder at the attempt, which was in itself worthless, and at the attempter, who, for fear rather than for love of his wife, failed to complete it. I praise a man who loves his wife as God ordains; but when he does not love her, I think little of him for fearing her."

"Truly," replied Parlamente, "if love did not render you a good husband, I should make small account of what you might do through fear."

"You are quite safe, Parlamente," said Hircan, "for the love I bear you makes me more obedient than could the fear of either death or hell."

"You may say what you please," said Parlamente, "but I have reason to be content with what I have seen and known of you. As for what I have not seen, I have never wished to make guess or still less inquiry."

"I think it great folly," said Nomerfide, "for women to inquire so curiously concerning their husbands, or husbands concerning their wives. Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof, without giving so much heed to the morrow."

"Yet it is sometimes needful," said Oisille, "to inquire into matters that may touch the honour of a house in order to set them right, though not to pass evil judgment upon persons, seeing that there is none who does not fail."

"Many," said Geburon, "have at divers times fallen into trouble for lack of well and carefully inquiring into the errors of their wives."

"I pray you," said Longarine, "if you know any such instance, do not keep it from us."

"I do indeed know one," said Geburon, "and since you so desire, I will relate it."

Footnotes:

- As Queen Margaret was by no means over fond of gorgeous apparel and display, this passage is in contradiction with M. de Lincy's surmise that the lady of this and the preceding tale may be herself. In any case the narrative could only apply to the period of her first marriage, and this was in no wise a love-match. Yet we are told at the outset of the above story that the lady and gentleman had married on account of the great affection between them. On the other hand, these details may have been introduced the better to conceal the identity of the persons referred to.— Ed.

- The French expression here is femme de chambre à chaperon. The chaperon in this instance was a cap with a band of velvet worn across it as a sign of gentle and even noble birth. The attendant referred to above would therefore probably be a young woman of good descent, constrained by circumstances to enter domestic service.—B. J. and Ed.

- This is probably a reference to the card game now called piquet, usually played for a hundred points. It is one of the oldest of its kind. See Rabelais' Gargantua, book i. chap, xxii.—L.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.