the Secretary Opening The Pasty

The Heptameron - Day 3, Tale 28 - the Secretary Opening The Pasty

TALE XXVIII.

A secretary, thinking to deceive Bernard du Ha, was by him cunningly deceived. (1) 1 The incidents of this story must have occurred subsequent to 1527. The secretary is doubtless John Frotté. We have failed to identify the Lieutenant referred to.—M. and Ed.

It chanced that when King Francis, first of the name, was in the city of Paris, and with him his sister, the Queen of Navarre, the latter had a secretary called John. He was not one of those who allow a good thing to lie on the ground for want of picking it up, and there was, accordingly, not a president or a councillor whom he did not know, and not a merchant or a rich man with whom he had not intercourse and correspondence.

At this time there also arrived in Paris a merchant of Bayonne, called Bernard du Ha, who, both on account of the nature of his commerce and because the Lieutenant for Criminal Affairs (2) was a countryman of his, was wont to address himself to that officer for counsel and assistance in the transaction of his business. The Queen of Navarre's secretary used also frequently to visit the Lieutenant as one who was a good servant to his master and mistress.

2 The Provost of Paris, who, in the King's name, administered justice at the Châtelet court, and upon whose sergeants fell the duty of arresting and imprisoning all vagabonds, criminals and disturbers of the peace, was assisted in his functions by three lieutenants, one for criminal affairs, one for civil affairs, and one for ordinary police duties.—Ed.

"What will you give me if I keep silence?"

Bernard du Ha, who was by no means so much afraid as he seemed to be, saw that the secretary was trying to cozen him, and promised to give him a pasty of the best Basque ham (3) that he had ever eaten. The secretary was well pleased at this, and begged that he might have the pasty on the following Sunday after dinner, which was promised him.

3 So-called Bayonne ham is still held in repute in France. It comes really from Orthez and Salies in Beam.—D.

Relying upon this promise, he went to see a lady of Paris whom above all things he desired to marry, and said to her—

"On Sunday, mistress, I will come and sup with you, if such be your pleasure. But trouble not to provide aught save some good bread and wine, for I have so deceived a foolish fellow from Bayonne that all the rest will be at his expense; by my trickery you shall taste the best Basque ham that ever was eaten in Paris."

The lady believed his story, and called together two or three of the most honourable ladies of her neighbourhood, telling them that she would give them a new dish such as they had never tasted before.

When Sunday was come, the secretary went to look for his merchant, and finding him on the Pont-au-Change, (4) saluted him graciously and said—

"The devil take you, for the trouble you have given me to find you."

4 The oldest of the Paris bridges, spanning the Seine between the Châtelet and the Palais. Originally called the Grand-Pont, it acquired the name of Pont-au-Change through Louis VII. allowing the money-changers to build their houses and offices upon it in 1141.—Ed.

Bernard du Ha made reply that a good many men had taken more trouble than he without being rewarded in the end with such a dainty dish. So saying, he showed him the pasty, which he was carrying under his cloak, and which was big enough to feed an army. The secretary was so glad to see it that, although he had a very large and ugly mouth, he mincingly made it so small that one would not have thought him capable of biting the ham with it. He quickly took the pasty, and, without waiting for the merchant to go with him, went off with it to the lady, who was exceedingly eager to learn whether the fare of Gascony was as good as that of Paris.

When supper-time was come and they were eating their soup, the secretary said—

"Leave those savourless dishes alone, and let us taste this loveworthy whet for wine."

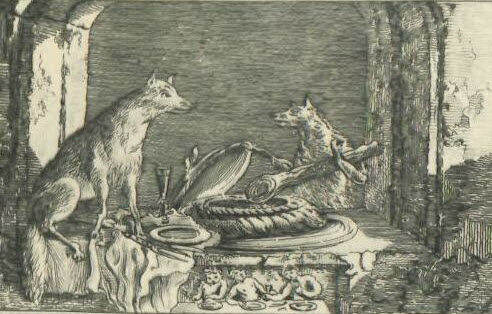

So saying, he opened the huge pasty, but, where he expected to find ham, he found such hardness that he could not thrust in his knife. After trying several times, it occurred to him that he had been deceived; and, indeed, he found 'twas a wooden shoe such as is worn in Gascony. It had a burnt stick for knuckle, and was powdered upon the top with iron rust and sweet-smelling spice.

Heptameron Story 28

If ever a man was abashed it was the secretary, not only because he had been deceived by the man whom he himself had thought to deceive, but also because he had deceived her to whom he had intended and thought to speak the truth. Moreover, he was much put out at having to content himself with soup for supper.

The ladies, who were well-nigh as vexed as he was, would have accused him of practising this deception had they not clearly seen by his face that he was more wroth than they.

After this slight supper, the secretary went away in great anger, intending, since Bernard du Ha had broken his promise, to break also his own. He therefore betook himself to the Lieutenant's house, resolved to say the worst he could about the said Bernard.

Quick as he went, however, Bernard was first afield and had already related the whole story to the Lieutenant, who, in passing sentence, told the secretary that he had now learnt to his cost what it was to deceive a Gascon, and this was all the comfort that the secretary got in his shame.

The same thing befalls many who, believing that they are exceedingly clever, forget themselves in their cleverness; wherefore we should never do unto others differently than we would have them do unto us.

"I can assure you," said Geburon, "that I have often known similar things to come to pass, and have seen men who were deemed rustic blockheads deceive very shrewd people. None can be more foolish than he who thinks himself shrewd, nor wiser than he who knows his own nothingness."

"Still," said Parlamente, "a man who knows that he knows nothing, knows something after all."

"Now," said Simontault, "for fear lest time should fail us for our discourse, I give my vote to Nomerfide, for I am sure that her rhetoric will keep us no long while."

"Well," she replied, "I will tell you a tale such as you desire.

"I am not surprised, ladies, that love should afford Princes the means of escaping from danger, for they are bred up in the midst of so many well-informed persons that I should marvel still more if they were ignorant of anything. But the smaller the intelligence the more clearly is the inventiveness of love displayed, and for this reason I will relate to you a trick played by a priest through the prompting of love alone. In all other matters he was so ignorant that he could scarcely read his mass."

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.