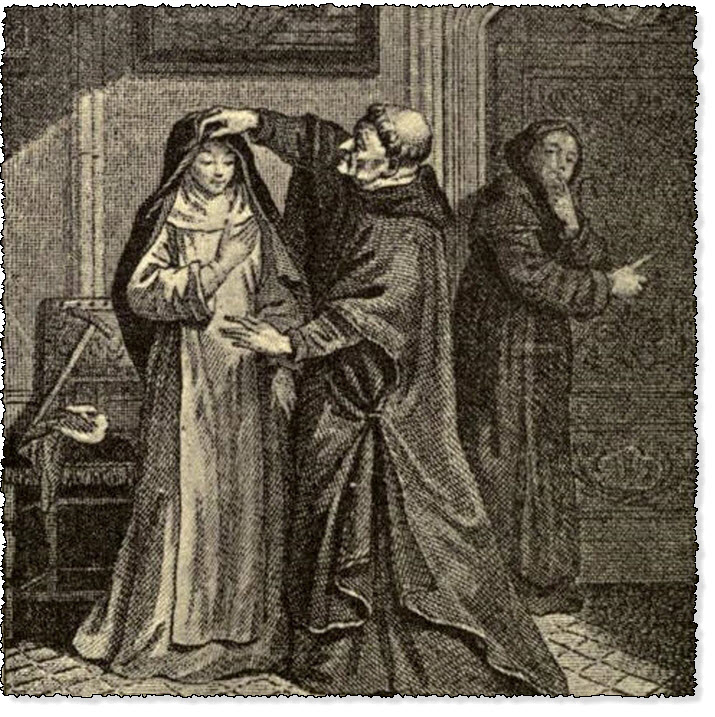

the Grey Friar Deceiving The Gentleman of Périgord

The Heptameron - Day 3, Tale 23 - the Grey Friar Deceiving The Gentleman of Périgord

TALE XXIII.

The excessive reverence shown by a gentleman of Périgord to the Order of St. Francis, brought about the miserable death of his wife, his little child and himself. (1) 1 Etienne introduces this tale into his Apologie pour Hérodote, ch. xxi.—B. J.

In the county of Périgord dwelt a gentleman whose devotion to St.Francis was such that in his eyes all who wore the saint's robe mustneeds be as holy as the saint himself. To do honour to the latter,he had caused rooms and closets to be furnished in his house for thelodgment of the brethren, and he regulated all his affairs by theiradvice, even to the most trifling household matters, believing that hemust needs pursue the right path if he followed their good counsels.

Now it happened that this gentleman's wife, who was a beautiful womanand as discreet as she was virtuous, was brought to bed of a fine boy,whereat the love which her husband bore her was increased twofold.One day, in order to entertain his dear, he sent for one of hisbrothers-in-law, and just as the hour for supper was drawing nigh, therearrived also a Grey Friar, whose name I will keep secret out of regardfor his Order. The gentleman was well pleased to see his spiritualfather, from whom he had no secrets, and after much talk among his wife,his brother-in-law and the monk, they sat down to supper. While theywere at table the gentleman cast his eyes upon his wife, who was indeedbeautiful and graceful enough to be desired of a husband, and thereuponasked this question aloud of the worthy father—

"Is it true, father, that a man commits mortal sin if he lies with hiswife at the time of her lying-in?" (2)

2 Meaning the period between her delivery and her churching.—Ed.

The worthy father, whose speech and countenance belied his heart,answered with an angry look—

"Undoubtedly, sir, I hold this to be one of the very greatest sins thatcan be committed in the married state. The blessed Virgin Mary would notenter the temple until the days of her purification were accomplished,although she had no need of these; and if she, in order to obey the law,refrained from going to the temple wherein was all her consolation,you should of a surety not fail to abstain from such slight pleasure.Moreover, physicians say that there is great risk to the offspring sobegotten."

When the gentleman heard these words, he was greatly downcast, for hehad hoped that the good Friar would give him the permission he sought;however, he said no more. Meanwhile the worthy father, who had drunkmore than was needful, looked at the lady, (3) thinking to himself that,if he were her husband, he would ask no Friar's advice before lyingwith her; and just as a fire kindles little by little until at last itenvelops the whole house, so this monk began to burn with such exceedinglust that he suddenly resolved to satisfy a desire which for three yearshe had carried hidden in his heart.

3 The French word here is damoiselle, by which appellation the lady is called throughout the story. Her husband, being a petty nobleman, was a damoiseau, whence the name given to his wife. The word damoiselle is frequently employed in the Heptameron, and though sometimes it merely signifies an attendant on a lady, the reference is more frequently to a woman of gentle birth, whether she be spinster, wife or widow. Only women of high nobility and of the blood royal were at that time called Madame.—Ed.

After the tables had been withdrawn, he took the gentleman by thehand, and, leading him to his wife's bedside, (4) said to him in herpresence—

"It moves my pity, sir, to see the great love which exists between youand this lady, and which, added to your extreme youth, torments you sosore. I have therefore determined to tell you a secret of our sacredtheology which is that, although the rule be made thus strict by reasonof the abuses committed by indiscreet husbands, it does not sufferthat such as are of good conscience like you should be balked of allintercourse. If then, sir, before others I have stated in all itsseverity the command of the law, I will now reveal to you, who are aprudent man, its mildness also. Know then, my son, that there are womenand women, just as there are men and men. In the first place, mylady here must tell us whether, three weeks having gone by since herdelivery, the flow of blood has quite ceased?"

4 The supper would appear to have been served in the bedroom, and the tables were taken away as soon as the repast was over. It seems to us very ridiculous when on the modern stage we see a couple of lackeys bring in a table laden with viands and carry it away again as soon as the dramatis personæ have dined or supped. Yet this was the common practice in France in Queen Margaret's time.—Ed.

The lady replied that it had.

"Then," said the Friar, "I permit you to lie with her without scruple,provided that you are willing to promise me two things."

The gentleman replied that he was willing.

"The first," said the good father, "is that you speak to no oneconcerning this matter, but come here in secret. The second is thatyou do not come until two hours after midnight, so that the good lady'sdigestion be not hindered."

These things the gentleman promised; and he confirmed his promise withso strong an oath that the other, knowing him to be foolish rather thanfalse, was quite satisfied.

After much converse the good father withdrew to his chamber, giving themgood-night and an abundant blessing. But, as he was going, he took thegentleman by the hand, and said to him—

"You too, sir, i' faith must come, nor keep your poor lady longerawake."

Thereupon the gentleman kissed her. "Sweetheart," said he, and the goodfather heard him plainly, "leave the door of your room open for me."

And so each withdrew to his own chamber.

On leaving them the Friar gave no heed to sleep or to repose, and, assoon as all the noises in the house were still, he went as softly aspossible straight to the lady's chamber, at about the hour when he waswont to go to matins, and finding the door open in expectation of themaster's coming, he went in, cleverly put out the light, and speedilygot into bed with the lady, without speaking a single word.

The lady, believing him to be her husband, said—

"How is this, love? you have kept but poorly the promise you gavelast evening to our confessor that you would not come here before twoo'clock."

The Friar, who was more eager for action than for contemplation, andwho, moreover, was fearful of being recognised, gave more thought tosatisfying the wicked desires that had long poisoned his heart than togiving her any reply; whereat the lady wondered greatly. When the friarfound the husband's hour drawing near, he rose from the lady's side andreturned with all speed to his own chamber.

Then, just as the frenzy of lust had robbed him of sleep, so now thefear that always follows upon wickedness would not suffer him to rest.Accordingly, he went to the porter of the house and said to him—

"Friend, your master has charged me to go without delay and offer upprayers for him at our convent, where he is accustomed to perform hisdevotions. Wherefore, I pray you, give me my horse and open the doorwithout letting any one be the wiser; for the mission is both pressingand secret."

The porter knew that obedience to the Friar was service acceptable tohis master, and so he opened the door secretly and let him out.

Just at that time the gentleman awoke. Finding that it was close on thehour which the good father had appointed him for visiting his wife, hegot up in his bedgown and repaired swiftly to that bed whither by God'sordinance, and without need of the license of man, it was lawful for himto go.

When his wife heard him speaking beside her, she was greatly astonished,and, not knowing what had occurred, said to him—

"Nay, sir, is it possible that, after your promise to the good father tobe heedful of your own health and of mine, you not only come before thehour appointed, but even return a second time? Think on it, sir, I prayyou."

On hearing this, the gentleman was so much disconcerted that he couldnot conceal it, and said to her—

"What do these words mean? I know of a truth that I have not lain withyou for three weeks, and yet you rebuke me for coming too often. If youcontinue to talk in this way, you will make me think that my company isirksome to you, and will drive me, contrary to my wont and will, to seekelsewhere that pleasure which, by the law of God, I should have withyou."

The lady thought that he was jesting, and replied—

"I pray you, sir, deceive not yourself in seeking to deceive me; foralthough you said nothing when you came, I knew very well that you werehere."

Then the gentleman saw that they had both been deceived, and solemnlyvowed to her that he had not been with her before; whereat the lady,weeping in dire distress, besought him to find out with all despatchwho it could have been, seeing that besides themselves only hisbrother-in-law and the Friar slept in the house.

Impelled by suspicion of the Friar, the gentleman forthwith went inall haste to the room where he had been lodged, and found it empty;whereupon, to make yet more certain whether he had fled, he sent for theman who kept the door, and asked him whether he knew what had become ofthe Friar. And the man told him the whole truth.

The gentleman, being now convinced of the Friar's wickedness, returnedto his wife's room, and said to her—

"Of a certainty, sweetheart, the man who lay with you and did such finethings was our Father Confessor."

The lady, who all her life long had held her honour dear, wasoverwhelmed with despair, and laying aside all humanity and womanlynature, besought her husband on her knees to avenge this foul wrong;whereupon the gentleman immediately mounted his horse and went inpursuit of the Friar.

The lady remained all alone in her bed, with no counsel or comfort nearher but her little newborn child. She reflected upon the strange andhorrible adventure that had befallen her, and, without making any excusefor her ignorance, deemed herself guilty as well as the unhappiest womanin the world. She had never learned aught of the Friars, save to haveconfidence in good works, and seek atonement for sins by austerity oflife, fasting and discipline; she was wholly ignorant of the pardongranted by our good God through the merits of His Son, the remission ofsins by His blood, the reconciliation of the Father with us through Hisdeath, and the life given to sinners by His sole goodness and mercy; andso, assailed by despair based on the enormity and magnitude of her sin,the love of her husband and the honour of her house, she thought thatdeath would be far happier than such a life as hers. And, overcome bysorrow, she fell into such despair that she was not only turned asidefrom the hope which every Christian should have in God, but she forgother own nature, and was wholly bereft of common sense.

Heptameron Story 23

Then, overpowered by grief, and driven by despair from all knowledge ofGod and herself, this frenzied, frantic woman took a cord from the bedand strangled herself with her own hands.

And worse even than this, amidst the agony of this cruel death, whilsther body was struggling against it, she set her foot upon the faceof her little child, whose innocence did not avail to save it fromfollowing in death its sorrowful and suffering mother. While dying,however, the infant uttered so piercing a cry that a woman who sleptin the room rose in great haste and lit the candle. Then, seeing hermistress hanging strangled by the bed-cord, and the child stifled anddead under her feet, she ran in great affright to the apartment of hermistress's brother, and brought him to see the pitiful sight.

The brother, after giving way to such grief as was natural and fittingin one who loved his sister with his whole heart, asked the serving-womanwho it was that had committed this terrible crime.

She replied that she did not know; but that no one had entered the roomexcepting her master, and he had but lately left it. The brother thenwent to the gentleman's room, and not finding him there, felt sure thathe had done the deed. So, mounting his horse without further inquiry,he hastened in pursuit and met with him on the road as he was returningdisconsolate at not having been able to overtake the Grey Friar.

As soon as the lady's brother saw his brother-in-law, he cried out tohim—

"Villain and coward, defend yourself, for I trust that God will by thissword avenge me on you this day."

The gentleman would have expostulated, but his brother-in-law's swordwas pressing so close upon him that he found it of more importance todefend himself than to inquire the reason of the quarrel; whereuponeach dealt the other so many wounds that they were at last compelled byweariness and loss of blood to sit down on the ground face to face.

And while they were recovering breath, the gentleman asked—

"What cause, brother, has turned our deep and unbroken friendship tosuch cruel strife as this?"

"Nay," replied the brother-in-law, "what cause has moved you to slaymy sister, the most excellent woman that ever lived, and this in socowardly a fashion that under pretence of sleeping with her you havehanged and strangled her with the bed-cord?"

On hearing these words the gentleman, more dead than alive, came to hisbrother, and putting his arms around him, said—

"Is it possible that you have found your sister in the state you say?"

The brother-in-law assured him that it was indeed so.

"I pray you, brother," the gentleman thereupon replied, "hearken to thereason why I left the house."

Forthwith he told him all about the wicked Grey Friar, whereat hisbrother-in-law was greatly astonished, and still more grieved that heshould have unjustly attacked him.

Entreating pardon, he said to him—

"I have wronged you; forgive me."

"If you were ever wronged by me," replied the gentleman, "I havebeen well punished, for I am so sorely wounded that I cannot hope torecover."

Then the brother-in-law put him on horseback again as well as he might,and brought him back to the house, where on the morrow he died. And thebrother-in-law confessed in presence of all the gentleman's relativesthat he had been the cause of his death.

However, for the satisfaction of justice, he was advised to go andsolicit pardon from King Francis, first of the name; and accordingly,after giving honourable burial to husband, wife and child, he departedon Good Friday to the Court in order to sue there for pardon, whichhe obtained through the good offices of Master Francis Olivier, thenChancellor of Alençon, afterwards chosen by the King, for his merits, tobe Chancellor of France. (5)

5 M. de Montaiglon has vainly searched the French Archives for the letters of remission granted to the gentleman. There is no mention of them in the registers of the Trésor des Chartes. Francis Olivier, alluded to above, was one of the most famous magistrates of the sixteenth century. Son of James Olivier, First President of the Parliament of Paris and Bishop of Angers, he was born in 1493 and became successively advocate, member of the Grand Council, ambassador, Chancellor of Alençon, President of the Paris Parliament, Keeper of the Seals and Chancellor of France. This latter dignity was conferred upon him through Queen Margaret's influence in April 1545. The above tale must have been written subsequent to that date. Olivier's talents were still held in high esteem under both Henry II. and Francis II.; he died in 1590, aged 67.—(Blanchard's Éloges de tous les Présidents du Parlement, &c., Paris, 1645, in-fol. p. 185.) Ste. Marthe, in his funeral oration on Queen Margaret, refers to Olivier in the following pompous strain: "When Brinon died Chancellor of this duchy of Alençon, Francis Olivier was set in his place, and so greatly adorned this dignity by his admirable virtues, and so increased the grandeur of the office of Chancellor, that, like one of exceeding merit on whom Divine Providence, disposing of the affairs of France, has conferred a more exalted office, he is today raised to the highest degree of honour, and, even as Atlas upholds the Heavens upon his shoulders, so he by his prudence doth uphold the entire Gallic commonwealth."— M. L. and Ed.

"I am of opinion, ladies, that after hearing this true story there isnone among you but will think twice before lodging such knaves in herhouse, and will be persuaded that hidden poison is always the mostdangerous."

"Remember," said Hircan, "that the husband was a great fool to bringsuch a gallant to sup with his fair and virtuous wife."

"I have known the time," said Geburon, "when in our part of the countrythere was not a house but had a room set apart for the good fathers; butnow they are known so well that they are dreaded more than bandits."

"It seems to me," said Parlamente, "that when a woman is in bedshe should never allow a priest to enter the room, unless it be toadminister to her the sacraments of the Church. For my own part, when Isend for them, I may indeed be deemed at the point of death."

"If every one were as strict as you are," said Ennasuite, "the poorpriests would be worse than excommunicated, in being wholly shut offfrom the sight of women."

"Have no such fear on their account," said Saffredent; "they will neverwant for women."

"Why," said Simontault, "'tis the very men that have united us to ourwives by the marriage tie that wickedly seek to loose it and bring aboutthe breaking of the oath which they have themselves laid upon us."

"It is a great pity," said Oisille, "that those who administer thesacraments should thus trifle with them. They ought to be burned alive."

"You would do better to honour rather than blame them," said Saffredent,"and to flatter rather than revile them, for they are men who have it intheir power to burn and dishonour others. Wherefore 'sinite eos,' andlet us see to whom Oisille will give her vote."

"I give it," said she, "to Dagoucin, for he has become so thoughtfulthat I think he must have made ready to tell us something good."

"Since I cannot and dare not reply as I would," said Dagoucin, "I willat least tell of a man to whom similar cruelty at first brought hurt butafterwards profit. Although Love accounts himself so strong and powerfulthat he will go naked, and finds it irksome, nay intolerable, togo cloaked, nevertheless, ladies, it often happens that those who,following his counsel, are over-quick in declaring themselves, findthemselves the worse for it. Such was the experience of a Castiliangentleman, whose story you shall now hear."

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.